© L'Elisir d'amore - Gran Teatre del Liceu Barcelona (2025) (c) A. Bofill

© L'Elisir d'amore - Gran Teatre del Liceu Barcelona (2025) (c) A. Bofill

It is unusual for an operatic production to remain in the repertory for more than forty years, and rarer still for it to continue looking fresh and youthful. This Elisir d’amore, which will occupy the Liceu throughout the Christmas season, has a long and distinguished history. In 1983 Barcelona’s Grec Festival presented a staging of L’Elisir by Mario Gas in open-air performances; in the early 1990s it was revived at the Festival de Peralada; towards the end of that decade it was acquiredby the Liceu, re-worked, and presented during the seasons housed at the Teatre Victòria while the opera house was being rebuilt after the fire of 1994. Adapted to the characteristics of the current stage, it returned in 2005, 2012, 2013 and 2018.

The secret of such longevity is simple enough: a clever production that flows with ease. It ishumorous and theatrically assured, built upon a popular yet relatively minor title – one with no aura of myth about it,which does not tempt ambitious stage directors into displays of conceptual grandstanding.

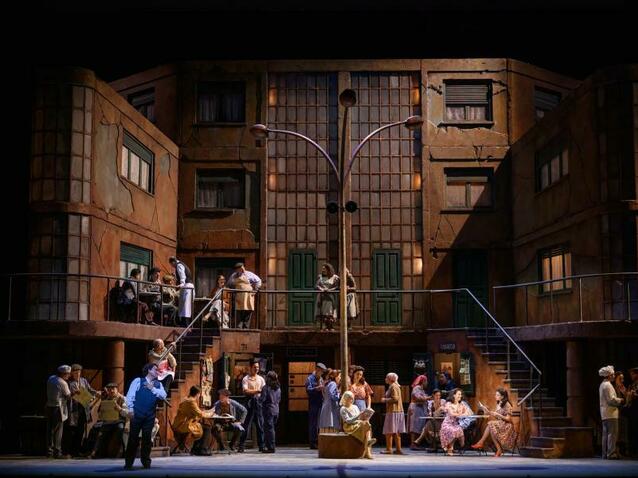

Gas sets the action in Italy, in a suburban, working-class district in the mid-1920s. The wonderfully crafted set, which embraces the characters, supports the singers by projecting the voice outwards and provides an upper gallery for the chorus. Itpresents vaguely “rationalist” buildings, already somewhat weathered, in a neighbourhood where life takes place in the square. The production has an unmistakable Fellini air and appears, in particular, as an homage to Amarcord, which had been released in 1973.

Gas regards his characters with tenderness. Through the histrionic, hyperactive and chattyDoctor Dulcamara he evokes the commedia dell’arte; through Sergeant Belcore he connects with classical comedy, the braggart, incompetent soldier being another reincarnation of Plautus’s miles gloriosus. Yet the central couple place the piece firmly within sentimental comedy, resting on a gentle, conventional, amiable, predictable romanticism – sweetened and already transmuted into an idealised point of reference for popular notions of courtship, allowing audiences to escape briefly from the fundamental mediocrity of their own lives.

Running beneath Gas’s approach is a vein of melancholy, a yearning for a lost paradise that never was. That melancholy is multiplied a thousand-fold for those of us who attended the première of this Elisir in 1983, have savoured all its many revivals, and now witness how the production remains fresh and youthful whilewe age.

L'Elisir d'amore - Gran Teatre del Liceu Barcelona (2025) (c) A. Bofill

The opening night brought a surprise: the Mexican tenor Javier Camarena, indisposed, was unable to sing and had to be replaced in the role of Nemorino by the New Zealander Filipe Manu, one of three tenors alternating in the fifteen performances scheduled for the coming days. Manu, who won the 2024 Tenor Viñas Competition – held annually at the Liceu– possesses a light-lyric tenor voice ideal for the role, with an attractive middle and upper register but a rather limited, underpowered lower range, fortunately little needed in this score. He phrases with taste and style, though his projection remains modest and needs improvement. Manu delivered the character well. Nemorino is simple and ingenuous, though not the half-wit he is often made out to be.

Adina was sung by the Barcelona soprano Serena Sáenz, who was vocally splendid. She ascends to the upper register with ease and brightness, entirely assured, while her middle voice is warm and her phrasing sweet and stylistically refined. She hasa voice that reaches out and embraces the listener. Her acting was consistently effective but rose to another level at the end, when she could reveal the enamoured woman. Her “Prendi, per me sei libero” was impeccably delivered.

Belcore was handled with panache, a fine voice, excellent projection and an effective touch of caricatural comedy by the young British baritone Huw Montague Rendall, making his Liceu début. One hopes to see and hear him again soon.

Having Ambrogio Maestri as Dulcamara was a luxury. The Pavia-born singer, who had already taken part in earlier revivals of this staging, still commands an imposing projection, a flawless canto silabato worthy of the best basso buffo tradition, and a volcanic and easy stage presence that meant he stole the spotlight whenever he appeared.

Anna Farrés offered a very fine Gianetta, and the chorus– benefiting from the set design and from a meticulous stage direction – delivered an excellent performance.

The musical direction was entrusted to Diego Matheuz, the Venezuelan conductor who, a decade ago, led another Donizetti opera at the Liceu, Don Pasquale, with unremarkable results. Matheuz has improved: he handles the orchestra better and drew particularly fine playing from the woodwinds. Yet he did not always coordinate adequately with the singers and should have moderated the orchestral sound in certain passages where it overwhelmed the voices. Donizetti is, above all, a vocal composer, which makes him a demanding author for conductors, who must support the singing, cushion it and remain discreetly in the background.

Xavier Pujol

Barcelona, 22ndNovember 2025

L’elisir d’amore, by Gaetano Donizetti. Serena Sáenz, soprano. Filipe Manu, tenor. Huw Montague Rendall, baritone. Ambrogio Maestri, bass. Anna Farrés, soprano. Orchestra and Choir of Gran Teatre del Liceu. Diego Matheuz, conductor. Mario Gas, stage director. Leo Castaldi, restaging. Marcelo Grande, scenography and costumes. Quico Gutiérrez, lighting. Production of the Gran Teatre del Liceu.

the 24 of November, 2025 | Print

Comments