© DR

© DR

Whether for its tunes among the most popular in the repertoire or its political dismension (the Italians, at the time under the domination of the Austrians, see themself in the Hebrews enslaved by the Assyrians in the libretto), Nabucco is a particularly emblematic opera. And it is almost more for its music, which gives a major part to the choir, going away from the romantic bel canto tradition to invent new rules focusing more onto the drama.

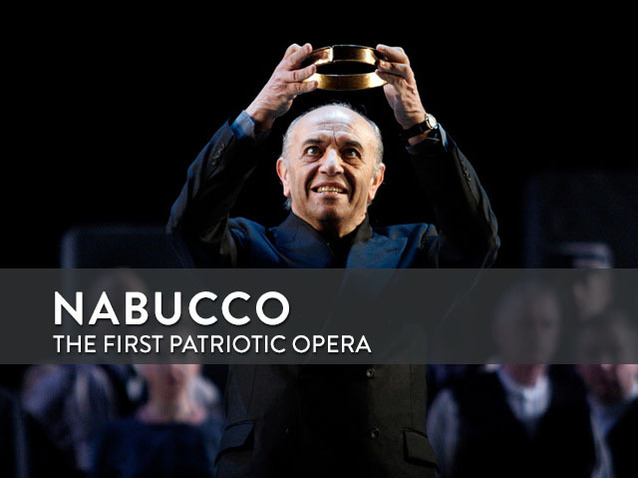

Starting Monday 6 June, the Royal Opera House of London revives the production set by Daniele Abbado (who transposes the biblical libretto just after the end of the World War II), with Placido Domingo and Liudmyla Monastyrska - whose performance of June 9 will be broadcasted live and for free on the Youtube channel of Covent Garden. To understand it better, we take the opportunity to study the historical context and the issues of Verdi's work.

***

My artistic career really began with “Nabucco”. So stated Verdi forty years after the debut of his third opera, and his first true success. A seminal work marked by a resolutely new style, Nabucco is far from the formalism that had until then kept the characters enclosed within a predetermined musical template. Opera became “theatre” by favouring the continuity of the action and the evolution of the protagonists. The demands of dramatic art infuse new life into the singing, the orchestra and the choruses, which now incarnate powerful ideals. Although Nabucco is one of Verdi’s most popular works, it is not his best known. Universally famous for its Hebrew chorus, in it we can glimpse Verdi’s compositional principles at their inception.

From Despair to Triumph

How can we explain the sudden appearance of a masterpiece that met the audience’s expectations right from the start? Is it possible to understand exactly how such a fortuitous match was suddenly achieved between a composer and his era? And we should avoid offering the facile, shorthand answers that are always favoured by a posteriori reconstructions. What can we say about Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) who triumphed at La Scala on the evening of 9 March 1842 with Nabucco? Many years later, the maestro, covered in glory and honours, tells the story of Nabucco’s genesis in his correspondence. His autobiographical narrative is undoubtedly too carefully “orchestrated” to correspond completely to the truth. But in his novelistic disclosures, we can feel the despair of a man who would lose his two young children and his wife, Margherita, in the space of just a few months. The novice composer, esteemed by his peers, could have given up his career then and there. In addition to the family tribulations he was experiencing, there was the failure of his second opera, King for a Day, whichfell into oblivion after a single performance at La Scala on 5 September 1840. “I was alone! Irredeemably alone! (…) May family had been wiped out!... And to keep the commitment I’d made. at that very painful moment in my life, I had to write am opera buffa!... ‘King for a Day ’ was not liked(…). Tormented by my family woes, which the failure of my work only exacerbated, I was convinced that art would never bring me solace, and I decided to stop writing music!....” Verdi would remain out of commission for two years; in Milan, he led an almost wretched life, supported by music lessons.

The composer overcame his immense suffering and seized an opportunity offered him by a chance meeting. One dreary winter evening, he crossed paths with the director of La Scala, Bartolomeo Merelli (1794-1879), who insisted on giving him a manuscript that had just been rejected by Otto Nicolaï (1810-1849), a composer now long forgotten. Nabucchodonosor is a libretto written for him by Temistocle Solera (1815-1878), reprising a piece by Francis Cornue and Anicet-Bourgeois (1836), already adapted for La Scala in the form of a ballet. Libretto, costumes, sets: everything was ready. The only thing lacking was inspiration, which suddenly burst forth, as Verdi describes it: “Once I was back home, I threw the manuscript violently on the table, and I stopped short. The manuscript fell open(…) My eyes fell on the page in front of me, and I read the verses:”Va pensiero, sull’ali dorate…” (…) I went to bed!...There was no escape…’Nabucco’ was still dancing through my head. Yet writing the work proved not to be so easy. Verdi did not have Rossini’s facility… The score was completed in autumn 1841 but Merelli quibbled – and Verdi grew impatient!

An essential step in his musical career, Nabucco also marked a crucial stage in Verdi’s personal life. Merelli asked him to seek out the opinion of La Strepponi, Milan’s most famous singer. Giuseppina Strepponi (1815-1897) was immediately enthusiastic. She persuaded Merelli to stage the opera and also to give her the female lead role of Abigaille. A few years later, Giuseppina became Verdi’s companion, and then his wife.

“Va pensiero sull’ali dorate…” (“Go, my thoughts, on your gilded wings…Fly to the beautiful homeland I have lost…”). A first reading of the libretto led Verdi to view these verses as more than a simple paraphrase of the Old Testament, which he studied faithfully. Is there anyone not familiar with what was to become the most famous chorus in the opera repertory? Verdi presents it to us as the true matrix of his work. The composer establishes a parallel between the situation of the Hebrews held captive in Babylon and that of Italy occupied by the Austrians. Aware of the collective drama his country was experiencing, Verdi managed to overcome his own personal drama by giving the oppressed patriots a magnificent song of hope that would echo until victory, the final unification of Italy in 1861. The night of the premiere at La Scala was a spectacular form of revenge for the musician, whose work as a triumph. The “Va pensiero” was encored. The audience was galvanised, and as the curtain fell they shouted “Freedom for Italy” and booed the Austrian oppressors. The Italians recognised themselves in the misfortunes of the Hebrew people held captive by the Assyrians, who were of course likened to the Austrian occupiers. Though only eight performances were planned, Nabucco was performed fifty-seven times at La Scala in three months. That is still the record.

In the wake of the amazing success achieved by Nabucco, Verdi came to be known as the “maestro del core”. Before him, choruses appeared mainly as a decorative interlude: the chorus often served to support the soloists with whom it dialogues; sometimes this is simply a way to create a pause in the flow of the opera to give the singers a rest, and the audience then gets to enjoy a refreshment in the loges.With no dramatic function, it was not until Verdi that the chorus came into its own, playing a real role, mainly in patriotic operas.

To some extent, this chorus of the Hebrews proved harmful to Nabucco. It was so liked and popular that some wanted to make it Italy’s national anthem, and it was recorded on its own an impressive number of times; it was not until 1951 that the whole opera, Nabucco, was honoured with a recording! Paradoxically, everyone could hum “Va pensiero” without knowing the plot and the issues raised by a Biblical drama that presents the madness of a king and the struggle for power.

“To the Young Stranger”

In 1836 a work appeared entitled Philosophy of Music: Towards a Social Opera. Its author was one of the leading figures of the “Risorgimento “,Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872), who belongs alongside Garibaldi (1807- 1882), Cavour (1810-1861) and Victor-Emmanuel II (1820-1878) as one of the fathers of Italian unity. In his essay on Italian opera, Mazzini harshly criticised the operas being produced in his day, which paid too much attention to musical hedonism by favouring “momentary sensations” and a “pleasure that dies with the sounds”. The author gave the artists of his day an almost political mission: in his view, opera could and should contribute to the “renaissance” that marked the advent of a united Italian nation. For this purpose, Mazzini recommended more realism in the drama and an abandonment of vocal virtuosity in favour of the recitative, which enhances character development. He suggested expanding the orchestra’s role in order to boost the expressiveness of the singing and give more continuity to the action. For Mazzini, the work’s unity and coherence are essential; he calls for a chorus to be present, which would be: “a solemn and complete representation of the popular element”. Who might create this opera in a new genre? Rossini had abandoned the lyric stage, Bellini was dead and Donizetti took a different path… So how could he not be tempted to think of the young Verdi of Nabucco when Mazzini dedicated his musings: “To the young stranger who, perhaps, somewhere in our country, is driven by aspiration, as I write, and holds within him the secret of a musical era”?

The coincidence is quite remarkable: Mazzini’s musings seem to have been answered by the novelty of Nabucco in the aesthetic and historical landscape of the 1840s. It is sad to think that, on the threshold of the 21st century, there are no longer any politicians capable of combining a reflection on art with the ideal of freedom and unity. Without wishing to draw too facile a comparison of Mazzini the composer with the committed theoretician that he was, we find in Nabucco more than one aspect that points to a profound change in the lyric art.

Towards a New Lyric Drama

The libretto so skilfully crafted by Temistocle Solera was freely inspired by events described in the Old Testament. Only Nabucco is an actual historical figure – even though his madness and conversion seem somewhat unlikely. A prophet named Zaccaria actually existed, but not during the era of the king of Babylon. Ismaele, Fenena and Abigaille are invented characters, and the story is an extreme simplification of the Hebrews’ condition: their fate was not what was reserved for slaves. What does historical truth matter! The events engineered by Solera advance quickly, boosted by major coups de théatre in a simple and effective style that perfectly suited Verdi. The two men collaborated again on I Lombardi (1843), Giovanna d’Arco (1845) and part of ’Attila (1846). The composer wrote a very audacious score whose originality made it a success. While there is the traditional chopping up into scenes, arias and duets, we are struck by the great energy that the musician managed to instil in the whole. An irresistible epic breath suffuses the work, and the audience is carried away with the first few bars in a dramatic and musical construction that toppled conventions. Verdi favoured what he called “positions”, which is to say, powerful moments that give the drama its steady rhythm. The main characteristics of Verdi’s dramaturgy are present in Nabucco , which opened up an intense period of creative activity: no fewer than eleven works were produced in eight years, right up to Rigoletto (1851), where the ideal of music guided by changes in the drama and the characters’ evolution is fully realised.

The casting of the roles was another new aspect of Nabucco. Verdi moved away from the Romantic “bel canto” tradition by inventing new rules that favoured the plot. The tenor, who with a Bellini or a Donizetti would have played the lead, here became a secondary character, Ismaele. Together with a mezzo, Fenena, he formed the traditional pair of lovers who here find themselves relegated to the background. An anecdote has it that Verdi rejected the lovers’ duet that Solera proposed for the third act on the pretext that it “cooled” the action. The composer preferred the magnificent prophecy of Zaccaria. The effect is far more gripping: the prophetic bass faces off with the protagonist, Nabucco, the first of Verdi’s great baritones. The father, torn apart, in the grips of madness, is an early harbinger of Rigoletto and Boccanegra.

It is said that La Strepponi thrilled the La Scala audience when she debuted in the role of Abigaille, but that she lost her voice forever doing it. The role is highly demanding, and even stronger voices can be put to sorely tested. The score includes major new forms of writing. The choruses and an unleashed orchestra were to be dominated. It was also necessary to play on register deviations and be able to maintain a vocal line enhanced with perilous cabalettas.

From Lyric Fervour to Patriotic Fervour

Nabucco was a decisive moment in Verdi’s career: it symbolised a genuine renaissance and the start of a glory that would soon include its share of constraints when the famous “years of hardship” came along. Overwhelmed by success, the composer had to produce constantly to honour the commissions that poured in from all the opera houses in Italy.Nabucco is also a sign of Verdi’s “musical” commitment alongside the liberal patriots who turned his name into a political slogan, “Viva Verdi”, with the various letters of his name evoking the name of the unifying king: Vittorio Emanuele Re D’Italia. But Nabucco is more than just a fortuitous encounter between a genius composer and a political cause, however noble it may have been. Operatic fervour led to patriotic fervour. Verdi died on 27 January 1901. One month later, a huge crowd followed his body to the crypt at the Casa di riposo where he would lie with his wife, Giuseppina Strepponi. Leading the procession, 900 chorus members accompanied by the La Scala conducted by Arturo Toscanini paid final homage with “Va pensiero”.

Catherine Duault

the 03 of June, 2016 | Print

Comments