© Bill Cooper

© Bill Cooper

Giuseppe Verdi’s Don Carlo, which premiered in 1867 in Paris as Don Carlos, exists in several versions, and, depending on which is performed, is either his longest or one of his longest operas. Although the first performance was in French, Nicholas Hytner’s 2008 production for the Royal Opera, which represents a co-production with the Metropolitan Opera, New York and the Norwegian National Opera and Ballet, employs the Modena version of 1886. This is one of several to utilise an Italian libretto, with Achille de Lauzières and Angelo Zanardini having translated Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle’s original French version.

Set in sixteenth century Spain, and based on Friedrich von Schiller’s tragedy Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien of 1787, the story sees church and crown battle for supremacy as individuals are forced to choose between their private love and public responsibility. Don Carlos is the son of King Philip II of Spain, and falls in love with the French Princess Elizabeth of Valois. Philip, however, rules that he shall marry Elizabeth himself and, because this would secure peace between the two warring nations and alleviate many people’s suffering, Elizabeth agrees. As he mourns his loss, Carlos’s friend Rodrigo, Marquis of Posa, persuades him to find his purpose by championing the cause of Flanders, a nation that Philip rules cruelly.

When Posa himself petitions the King, Philip insists that oppressing Flanders is the only way to maintain stability. He is, however, so impressed with Rodrigo’s outspoken courage that he takes him into his confidence, asking him to spy on his wife and son as he suspects there is something between them. His suspicions are supposedly confirmed after Princess Eboli, an aristocrat at court, takes action in revenge for Carlos loving Elizabeth rather than herself. As Philip grows increasingly desperate he seeks the advice of the Grand Inquisitor who grants him permission to kill his son, but demands that in return the King hand Posa over to the Inquisition. At this point, Philip favours dropping the matter altogether, but Rodrigo is killed after deliberately taking the blame for the Flemish rebellion so that Carlos may live to help Flanders. When, however, the latter says his farewells to Elizabeth as he plans to leave to fulfil his mission, the King and Grand Inquisitor move in on him. At the same time, the dead Emperor Charles V rises from his tomb to declare that suffering is unavoidable and ceases only in heaven.

Brian Jagde (Don Carlos), Lise Davidsen (Elizabeth of Valois), ROH Don Carlo © Bill Cooper

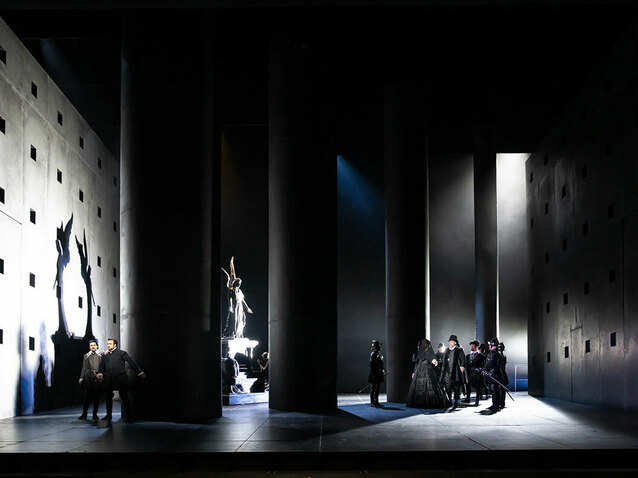

In Nicholas Hytner’s production, which is now enjoying its fourth revival (by Dan Dooner), Bob Crowley’s sets seem to combine realism, formalism and expressionism. For example, Act I takes place in the snow covered Forest of Fontainebleau. While, however, tall thin trees cover the stage, they are framed by a series of rectangular arches that suggest we are gazing in on a scene. Alongside this, the path through the snow follows an obvious and hence more stylised zig-zag pattern.

Some sets generate much atmosphere so that Charles V’s imposing tomb, clearly designed to intimidate anyone who kneels before it, is bathed in huge shafts of light, courtesy of Mark Henderson. When the chiaroscuro effects that are generated combine with the image of monks crossing the stage, the aesthetic feels highly reminiscent of the Spanish Renaissance. In particular, it brings to mind the works of Francisco de Zurbarán, actually born in the year Philip II died, whose painting of Saint Francis of Assisi is currently in an exhibition on the figure at London’s National Gallery. As the tomb then moves across the stage our eyes are drawn to a diagonal row of columns that, through manipulation of their respective sizes, appear to run to quite a depth.

The costumes are largely sixteenth century, although the heretics’ robes actually have flames imprinted upon them, but the sets do not stand in one specific era with some of their features feeling decidedly modern. In many ways they are designed to bring out certain points so that as Philip II encounters Rodrigo, his advance towards him appears to imitate the various diagonals that can be seen. The intended effects generally work well, although sometimes the attempts to create sets that feel large enough to suit this grand opéra make them feel a little too bold and hence sterile. For example, in Act III when the heretics are sent to be burnt at the stake, a huge, crude image of Christ’s face contrasts poorly with the rich golden facade of Valladolid Cathedral in the background, thus giving the scene insufficient gravitas. This said, the almost garish quality of the image does much to highlight just how sickening what is being done to these men in the name of God really is. The attention to detail here is also strong as one column on the facade is missing its capital, thus applying a touch of realism to a building that was so clearly designed to inspire awe.

The whole of Act IV takes place in the same austere, box-like area, in spite of it portraying both King Philip’s study where he meets with the Grand Inquisitor, and the prison in which Carlos is held. The implication is that Philip is as much a prisoner to the church as Carlos is to his father, with the windows that line the walls suggesting that there are opportunities for Carlos to get out and help Flanders, even if their minuscule size mean these are small.

John Relyea (King Philip II), ROH Don Carlo © Bill Cooper

Bertrand de Billy, who also conducted the last revival here in 2017, delivers a masterly reading of the score as the precision and balance that he achieves walk hand in hand with an exquisite capturing of the hues and colours that generate atmosphere at every turn. The cast is also outstanding with Brian Jagde as Carlos revealing an expansive and aesthetically pleasing tenor, and Luca Micheletti as Posa displaying a baritone that possesses sufficient depth and also quite a vibrant quality. Yulia Matochkina, with her impassioned mezzo-soprano, makes a thrilling Royal Opera debut as Princess Eboli, while there is excellent support from Alexander Köpeczi as the Monk, who all believe to be the supposedly dead Charles V, Ella Taylor as Tebaldo and Michael Gibson as the Count of Lerma. Despite only being heard at the end of Act III, and even then from offstage, Sarah Dufresne, with her beguiling soprano, leaves quite an impression as the Voice from Heaven, while the six Flemish Deputies are especially well sung by Josef Jeongmeen Ahn, Matthew Durkan, Felix Kemp, Dan D’Souza, Jihoon Kim and Simon Wallfisch.

John Relyea is a revelation as King Philip II, with his strong and secure bass possessing the right level of nuance, and his demeanour suggesting a man who is genuinely weighed down by the burdens that come with his position and personal circumstances. His encounter with the Grand Inquisitor is one of the highlights of the evening as Taras Shtonda uses his formidable bass to make us truly believe that a blind and ageing man who constantly looks on the brink of collapse could wield a level of power that puts even the King in fear and awe of him. First among equals, however, is Lise Davidsen whose soprano conquers every demand that the role of Elizabeth of Valois makes so seemingly effortlessly that it becomes easy for us to be drawn in by the emotions that she readily brings to bear. With immaculate phrasing and strong expressions and gestures, this is a performance that delivers on all fronts.

By Sam Smith

Don Carlo | 30 June - 15 July 2023 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 02 of July, 2023 | Print

Comments