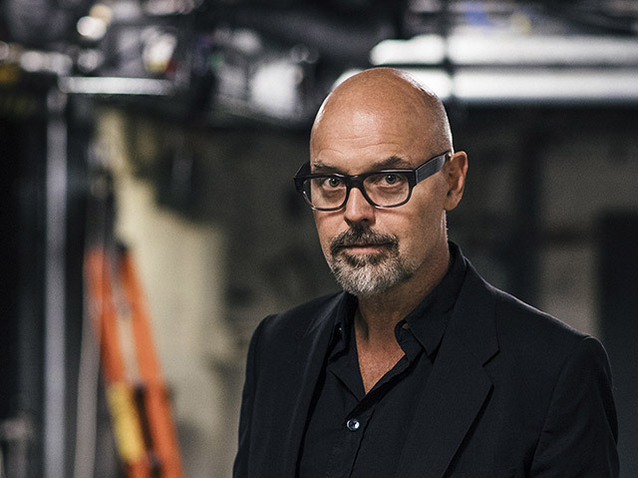

© (c) Love Strandell

© (c) Love Strandell

Jonas Söderman Bohlin composed the music and co-wrote the libretto of Tristessa, a brand new opera premiered at the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm last week. The work is based on The Passion of New Eve, a book written by Angela Carter in the late 70s. It tells the story of Evelyn, an aggressive man who will become a woman against his will through the action of a feminist cult. He worships Tristessa, a Golden Age movie star that will eventually share his destiny. We discussed the making of the opera with Jonas Söderman Bohlin after the second function of Tristessa this week.

***

The Royal Swedish Opera commissioned Tristessa from you in 2011. How were you approached and what were the guidelines of the project?

Jonas Söderman Bohlin: It wasn’t exactly a commission from the Royal Opera because we came up with the idea and brought it to them. Torbjörn Elensky (the co-librettist) found the book from the beginning because he wrote the preface for the first Swedish translation. He called me in the subway and told me “I have an opera idea!”. I had already worked with him on several projects, as well as with Ann-Sofi Sidén (in charge of video design), whom I decided to contact. The topics raised in the opera are sensitive in the contemporary society. Many people have had really bad experiences to be queer or different. It was then very important for all of us to describe this situation with a lot of respect. If you make this too easy or simplify the question, it goes totally wrong, and I knew Ann-Sofi Sidén would have a real sense of balance.

There is much room for video design in Tristessa. As a film music composer, did you have a different approach on this work? And how did you do to make the video, libretto and music live together?

Jonas Söderman Bohlin: Ann-Sofi, Torbjörn and I worked quite closely in the first years of the stage adaptation of the book. The images came quite early in the process. I had them in my head when I was writing the music, so I absolutely sticked to them like in film music. There is no lead theme or character. The music is always contextual for what’s happening on stage and for what the different characters are going through, like a photograph captured in real time.

For me, the libretto needed to be novelistic as there is no dialogue in the original book. All dialogues here were created and some excerpts were taken directly from the book. It’s quite a challenge for the singers to sing about these issues. The author only describes, she gives no opinion and offers no solution to handle this. That’s what we’ve been trying to do also on the libretto because you can’t have an opinion, but only respect the experience of everyone living this life individually. You can’t make it general.

How far were you influenced by the Me Too movement (a global movement against sexual harassment and sexual assault, mainly on women, that went viral on social media from October 2017) during the creation process?

Jonas Söderman Bohlin: It’s important to point out that the opera was finished in 2016, so at least one year before the Me Too movement. Everything was already engaged with the Kungliga Operan before the events. Some people in Sweden make a political connection to the opera, but this is not our intention. Of course, the issue was a major concern before Me Too, but the movement highlighted the abuses women suffer from in the whole world. We had already started the creation process and the topic became so sensitive that I wondered if we’d have the courage to accomplish it till the end. Birgitta Svendén, the general manager of the Royal Swedish Opera, encouraged us to continue with the same perspective. We talked about that a lot during the rehearsals but we did not have to change anything in the libretto. I think Katharina Thoma (the director) could make all the decisions she had initially planned about the powerful and bold graphic dimension. The novel is from 1977 but is still provocative. It‘s not just about women being good and men being evil. Women can also be evil too and capable of sexual abuse. The story is so strange and surrealistic that it might have more impact on spectators after Me Too.

Three singers have both the role of a man and a woman in the opera. How did you integrate the gender question into the music, additionally to the role shares?

Jonas Söderman Bohlin: What you mention is the most important thing, according to me. I don’t know what kind of music should reflect gender. But I was very influenced by the novel, the way Angela Carter worked with the extremes. It’s always very high and low. Sometimes you have colourful imagery and sometimes it gets to raw and direct language. This is something I was very inspired by for the music. And I love eclectic music. I’m tired of modernistic music so I I wanted to do something totally different and work with major and minor harmony, but not in the traditional way. There is a change of feelings and expressions between the distinct characters interpreted by the same singers. For example, that’s quite clear that Tristessa is calm and even fragile whereas Evelyn is fiery and violent. I chose to develop chord progressions and explore tonalities. In Tristessa the key changes in every bar, there is no chord resolution, it is a continuous cadence.

In Nixon in China and I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky, John Adams evokes actual facts through the music he composed. How did you integrate contemporary issues into the music of Tristessa?

Jonas Söderman Bohlin: I think the music of the opera is contemporary in every aspect. In the way I see things, it’s a common misunderstanding or mistake to say that as soon as you use major and minor tonalities you compose classical music and not contemporary music. I think John Adams is a very interesting composer, I really like Thomas Adès too. I wanted to make music that could be exoteric and not esoteric, with singular harmonics. I focused rather on the feelings, which are really concrete. The surrealistic part is here, but the characters are definitely real. For example, Zero and the seven women have no psychological depth. They’re standing for people who don’t respect or accept people with another sexual identity. This is why I used a single theme that I developed in many ways in the second act. The other characters carry much more complexity. Angela Carter brought stereotypes on the surface but below the surface lies something more subtle. I wanted to illustrate that through the music. In the second part, Eve's journey leads to the acceptance of her new body for the first time. I think this is the main story of Tristessa.

Interview carried out in Stockholm by Thibault Vicq

Photo copyright: Love Strandell

the 11 of October, 2018 | Print

Comments