Faust, The Royal Opera © 2025 Marc Brenner

Faust, The Royal Opera © 2025 Marc Brenner

Charles-François Gounod’s Faust, with a libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, premiered at the Théâtre Lyrique on the Boulevard du Temple in Paris on 19 March 1859. It underwent several revisions over the following decade, including the insertion of a ballet into Act V to meet the expectations of grand opera, and was extremely popular in the nineteenth century. It was the work with which New York’s Metropolitan Opera opened for the first time on 22 October 1883, while Covent Garden included it in its programme every year until 1912. Today it may not be performed with quite the same frequency, but it has retained enough appeal to ensure that it graces most major opera houses at least once every few years.

The story is derived from Carré’s play Faust et Marguerite, which in turn is loosely based on Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust, Part I. While Goethe’s play is in two parts, the decision to focus on the first derived from it containing the more dramatic subject matter, and the same approach was adopted by Hector Berlioz in his slightly earlier ‘légende dramatique’, La damnation de Faust (1846). However, Mefistofele (1868) by Arrigo Boito, better known today as Verdi’s librettist for Otello and Falstaff, covers both as it includes Faust’s encounter with Helen of Troy that constitutes one of his adventures in the ‘macrocosmos’, while Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 in E flat major (1910) uses the words of Part II’s final scene.

The Metropolitan Opera’s most recent production of the opera saw director Des McAnuff situate Faust’s study beneath an A-bomb, hinting at the doctor’s destructive thirst for knowledge that is so prevalent in Christopher Marlowe’s ‘original’ telling of the tale. David McVicar’s 2004 version for the Royal Opera, which is revived on this occasion by Peter Relton, keeps the concept much closer to Gounod’s original, with Faust’s search being (in origin, at least) for youth, and Marguerite acting as either the catalyst or the bait.

David McVicar's production of Gounod's Faust, The Royal Opera ©2025 Marc Brenner

Charles Edwards’ set consists of a dilapidated, half gilded theatre on one side of the stage, and the arches of a Gothic vaulted church on the other. In this way, the dichotomy between temptation and virtue is made clear, and with theatre curtains, Marguerite’s humble dwelling and prison bars falling between the two across the various scenes, the idea that all life plays out between the earthly and the spiritual comes into focus.

The way in which the light, courtesy of Paule Constable, falls on the prison bars is especially effective, and illustrates how McVicar’s strong overarching concept is complemented by an exquisite attention to detail that ensures maximum dramatic impact. As an old man at the start, Faust is dressed in red so that, with the chiaroscuro lighting, he could almost be St Jerome in a painting by Caravaggio. The theatre as a place of transitory delights is a recurring motif, and when Méphistophélès takes Faust to the Harz mountains on Walpurgis Night the stage’s backdrop reveals the auditorium to the Royal Opera House. Faust undergoes his transition to a young man when a theatrical trunk is opened up to create a dressing area, with the mirror on its inside lid finding a parallel with the one that Marguerite finds in her box of jewels.

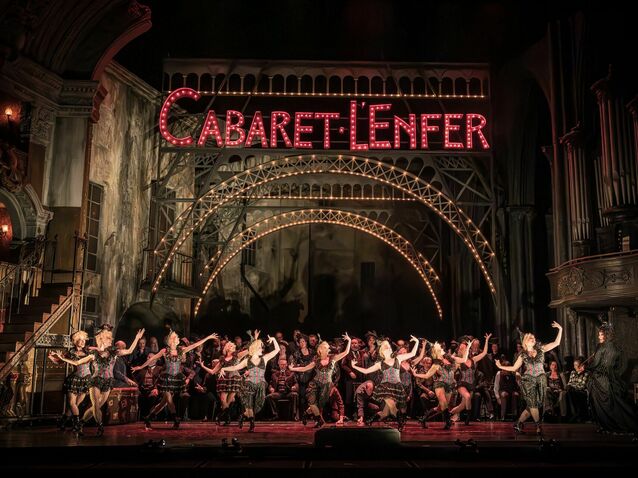

There is a suitable dose of flamboyance in Act II’s flag waving scene, and the subsequent dancing of ‘Ainsi que la brise légère’, courtesy of Michael Keegan-Dolan and revival choreographer Emmanuel Obeya, in a venue entitled ‘Cabaret L’Enfer’. Nevertheless, even in the more exuberant moments the sinister undertones are brought into sharp focus. When in Act II Méphistophélès supplies the crowd with wine, he pierces the side of a statue of the crucified Christ in order to obtain it. Similarly, Act V’s Walpurgis Night ballet is very poignant as it vividly describes the shaming of Marguerite and the fate of her brother Valentin.

Carolina López Moreno as Marguerite in David McVicar's production of Gounod's Faust, The Royal Opera ©2025 Marc Brenner

As Méphistophélès, Adam Palka replaces a previously advertised Erwin Schrott who played the role in the last revival in 2019. His bass is strong, warm and engaging, and while he does not possess the absolute bite and menace that some might seek in a portrayal, that actually produces dividends. When a youthful Faust prods him with a devil's fork, he reveals his irritation when any more pronounced a reaction would have simply made him comical. Similarly, when he sings the irreverent ‘Le veau d’or’ in Act II one can believe how the people listening would take him as a hearty charmer, and not realise just how sinister his intentions were. Ildebrando D'Arcangelo sings Méphistophélès for the final three performances in the run.

As Faust, Stefan Pop reveals a tenor that can be light and tender, but also forceful and impassioned. As Marguerite, Carolina López Moreno replaces Lisette Oropesa and displays a soprano that is as subtle as it is sumptuous. However, it is when the two work together that things rise to another level as Act III’s ‘Laisse-moi, laisse-moi contempler ton visage’ is extremely moving. One really senses that, while Faust will ultimately use Méphistophélès to obtain Marguerite, he would rather it was truly him winning her, and will go as far as he can to try to woo her unaided. The quartet singing in the act, which also involves Palka and Monika-Evelin Liiv as Marthe Schwertlein, is similarly exquisite, even though the second pair introduce elements of comedy and deceit. Boris Pinkhasovich’s Valentin and Hongni Wu’s Siébel are both beautifully sung, while there is strong support from Ossian Huskinson’s Wagner. In the pit Maurizio Benini achieves precise, insightful and engaging playing from the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, while the Royal Opera Chorus, under chorus director William Spaulding, delivers both balanced and stirring singing across the evening, especially in the men’s ‘Gloire immortelle de nos aïeux’.

By Sam Smith

Faust | 23 May - 10 June 2025 | Royal Ballet and Opera, Covent Garden

the 28 of May, 2025 | Print

Comments