© DR

© DR

Kurt Weill’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny is something of an operatic oddity. It describes the establishing and subsequent implosion of a city that is designed to give people fun because, as its founders assert, there is nothing else in the world to rely on.

Weill and librettist Bertolt Brecht were writing predominantly about the world they saw around them in 1930, but their depiction of Mahagonny, and by extension society in general, feel highly relevant today. They were also far too clever to make their depiction of the city anything other than highly ambiguous. It is initially founded by three fugitives (Begbik, Fatty and Trinity Moses) who find themselves unable to flee any further from the pursuing federal agents. They then attract people disillusioned with their own lives, including four Alaskan lumberjacks led by Jimmy McIntyre.

For a period, life is tranquil in Mahagonny, but this irritates both the fugitives, because people are leaving through boredom which is hitting their profits, and the restless Jimmy. He declares that everything should be permitted, and when an impending typhoon not only misses Mahagonny, but also hits the federal agents who were chasing the fugitives, everyone is converted to his philosophy. However, the pleasures that Jimmy advocates (eating, loving, fighting and drinking) actually come into direct conflict with a lust for money, and he is finally tried and executed by the city not for introducing unrestrained hedonism, but for failing to pay his bar bill.

In this new production, the first ever at the Royal Opera House, director John Fulljames updates the scenario to the present day (or even 2020) and tells us that we are not so much entering an auditorium as Mahagonny itself. Before the curtain has even risen projections inform us of what is and isn’t permitted, and alert us to relevant apps. Then through clever camera work we all become complicit in Jimmy’s execution because surely any of us had the opportunity to bail him out.

In Act I the set is dominated by a lorry that alludes to the fugitives’ initial means of escape, as well as the contemporary issue of people trafficking. As it spins around, however, it becomes an all-purpose prop from which all of the action radiates. This helps to make the production feel slick, but it also asserts a great deal of control over the proceedings when the themes and the music demand a staging that allows the performers to be let loose just a little more.

Act II becomes racier as the people indulge in their four pleasures. The ending, however, is marred by sectioning the chorus off into different compartments within the set so that we only become truly overwhelmed when they leave these to confront us en masse. Clearly, Fulljames has a keen awareness of the need to pace the action, but sometimes it simply takes too long to reach any form of climax.

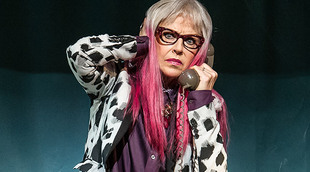

Musically the evening is strong, with Mark Wigglesworth conducting superbly, and the high calibre cast including Christine Rice whose mezzo-soprano as the whore Jenny is dark, rich, rounded and yet overwhelmingly feeling. Anne Sofie von Otter, Peter Hoare and Sir Willard White form an excellent triumvirate as the fugitives Begbik, Fatty and Trinity Moses respectively, while Jeffrey Lloyd Roberts, Darren Jeffery and Neal Davis excel as Jimmy’s friends. Kurt Streit as Jimmy puts in a fine vocal performance and if there are occasionally a few signs of strain, this hardly matters. His brand of charisma, however, falls between two stools. It is hard to sympathise with him as a ‘lost American soul’ on the one hand, or conversely to be moved by his charm when we see him acting so recklessly.

The performance is in English, utilising Jeremy Sams’ smooth translation, and it is no accident that ‘destroy the world’ is made to rhyme with ‘enjoy the world’. If the evening occasionally feels a little subdued, the control exerted over the production is remarkable in its own right, and manifests itself in the strong attention to detail, the lighting, the costumes and projections. Such elements should also come to the fore when the production is broadcast live to cinemas around the world on 1 April 2015.

By Sam Smith

Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny | 10 March – 4 April 2015 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 11 of March, 2015 | Print

Comments