© DR

© DR

Ravel’s L’heure espagnole and L’enfant et les sortilèges had been missing from La Scala stage for nearly 40 years, since 1978, when they had been presented as a diptych under George Prêtre’s baton. Their comeback in the production from the Glyndebourne Festival from 2012 (resumed in 2015) has been warmly welcomed by the Milanese audience as thoroughly enjoyable, brilliantly conceived entremets between the main courses of La fanciulla del West and Der Rosenkavalier. Both one-act shows worked as faultless theater machines, as perfectly winded as Torquemada’s clocks.

Laurent Pelly, who signed both stagings assisted by set designers Caroline Ginet and Florence Evrard (L’heure espagnole, originally seen under Seiji Ozawa in Tokyo and at Palais Garnier in 2004) and Barbara de Limbourg (L’enfant), served the audience a breathtaking visual impact. L’heure espagnole opens on the clockmaker’s shop & house: a room saturated to the brim with objects concealing clocks in every spot (even the washing machine) up to top of the tall wall the revealed when a colorful curtain opens as the action starts: a Dada obsession with the pivotal object of the play’s title which sheds a light of magic in the hyper-realistic setting as the clocks (in the company of a skeleton and a bicycle) get lit and start to move as in a frenzy(quite tellingly when Conception and Ramiro ascend to the lady’s quarters).

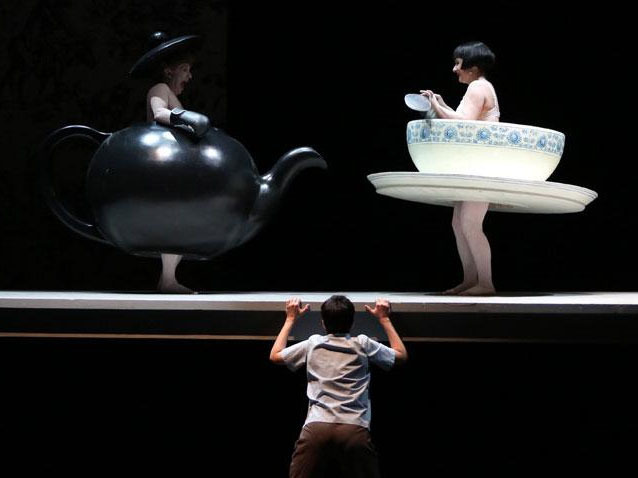

Much more than in recent stagings of the same work, magic is appropriately the main perspective of L’enfant’s production, powerfully amplified by De Limbourg’s sets and Pelly’s costumes. Right after the orchestral prelude, the Child’s world appears hauntingly oversized. L’Enfant sits on a two-meter tall chair doing his homework on a gigantic table, his mother moves three meters over the floor level, while all the animated objects, from the armchair to the giant spoon held by the China Cup, look uncomfortably large and threatening. The empty, black background boosts this awesome perception, leaving the frail body of the Child as the only steady visual point which the / in a magical visions turn around. In this general frame there is ample room for the amusing fox-trot involving the English Teapot and the China Cup, the upsetting Clock turning wildly and the obsessive math-lesson scene, recalling with its class of children in school uniform Laurent Tirard’s movie Le petit Nicolas, but also for the pure wonder of the cats’ duet, with the white moon cast against a blue sky. Magic is still the main perspective in the second tableau, the garden scene where nicely invented tree-men complain about their wounds, like in Vergil or Dante, in a dream-like atmosphere reminding a kind-hearted Janacek conjured by a slow waltz. The Child’s surprise gesture («He mended the injured paw») prompts an impressive, surprise scene of stillness and leads to the end of the story, with the Child’s Mother appearing behind the window on the background, significantly the only lit spot of the stage.

L’heure espagnole is a paradigm of perfect team-work. Each of the five characters, none of which can be considered a minor role, displayed a successful mixture of excellent acting (to which Pelly’s direction has dedicated specific care, envisioning a very effective rhythm in the coming-and-going of the characters in and out of the stage and a number of successful gags, as for instance with the two large Catalan clocks where Conception’s lovers take shelter) and enjoyable, secure singing. Fully plunged in Concepcion’s role was the energetic Stéphanie d’Oustrac, an imposing figure absolutely convincing in her attractive silhouette. Beautiful voices are shared by Jean-Luc Ballestra (Ramiro) and Yann Beuron (Gonzalve), the latter a very good actor in his funny hippie costume; an acting lesson came from Vincent Le Texier (Don Iñigo Gomez) as well, perfectly sporting his role of aged, gallant and overweight lover.

L’enfant et les sortilèges rests less on a team approach, being rather an ensemble work based on the polarity between a single soloist, the title role, and a group of 10 performers singing no less than 20 parts, not counting the choir and its soloists and the children’s choir instructed by Bruno Casoni. These forces shone in their roles and admirably fitted in the enchanting setting. Let us first single out the memorable acting of Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, performing the Tea-Pot, the Old Man teaching math and the Tree Frog, after being Torquemada in L’heure espagnole. Marianne Crebassa performed L’Enfant masterfully, always perfectly in tune and at ease in her part, to which provided an aggressive slant, yet quite restrained on the emotional side, as if the Child were not willing (or able) to express his true feelings freely and let them reach the audience in their most intimate nature.

Marc Minkowski, who led a memorable Lucio Silla at La Scala in 2015 (with an excellent Crebassa as Cecilio), conducts the entire diptych lending Ravel’s music a smooth, Debussyan sound, always flowing and subtly as if perceived behind a glass. Taste and measure always dominate; the orchestra – for all its fascination in the flaring moments – never sounds violent, but keeps constantly within civilized and elegant bounds. No orchestral effect, not even the harsher instrumental passages, is exaggerated or overdone; even the most lively, characteristic Spanish rhythms and the most blatant effects become transfigured in a dream-like atmosphere.

Raffaele Mellace

L'heure Espagnole / L'enfant et les Sortilèges at La Scala (june 2016)

the 06 of June, 2016 | Print

Comments