© Tristram Kenton

© Tristram Kenton

The Flying Dutchman, which premiered in Dresden in 1843, is the fourth of Richard Wagner’s thirteen operas, and considered to be his first mature one. This is because it is the first still to be regularly staged, with Wagner himself having ruled that the three that preceded it should never be performed at his Festspielhaus in Bayreuth. The composer had been inspired to write the opera following a stormy sea crossing he made from Riga to London in 1839, and the story is taken from Heinrich Heine’s retelling of the legend, which possibly originated in the seventeenth century, in his 1833 satirical novel Aus den Memoiren des Herrn von Schnabelewopski.

The Dutchman is cursed to sail the seven seas forever more for having once invoked Satan. However, every seven years he is able to come ashore, and if when he does so he can find a wife who will be true to him until death, his curse will be lifted. The opera focuses on one of these occasions when he lands on the coast of Norway and attempts to engineer a marriage with Senta, the daughter of the sea captain Daland whose ship he finds in the same port. Before they even meet, Senta has long thought about the Dutchman, whose picture has hung on her father’s wall, and longed to save him. Thus, their marriage seems assured, only Senta’s distraught former boyfriend, the huntsman Erik, reminds her of how she once vowed constancy to him. The Dutchman overhears this, and interprets it as meaning Senta would not remain true to him either. He therefore decides to release Senta from her promise and accept that he is lost forever, because were she to make her vow and then break it she would be eternally damned. Senta pleads with him in vain not to reject her, and after he departs she throws herself into the sea, thus securing the Dutchman’s redemption by ensuring she is true to him until death.

Elisabet Strid (Senta), Bryn Terfel (The Dutchman), The Flying Dutchman © ROH 2024. Photo by Tristram Kenton

Tim Albery’s production for the Royal Opera first appeared in 2009, and now enjoys its third revival. With everyone sporting twentieth century dress, courtesy of Constance Hoffman, it is strong at generating atmosphere, although there are a few flaws. For example, the Overture sees ripples sent across, and rain appearing on, the stage curtain, thus simulating a stormy sea. However, in spite of occasional flashes of lightning that illuminate the whole curtain, the movement simply feels too regular across the ten minutes, thus setting it at odds with all of the different themes and moods to be found in the Overture.

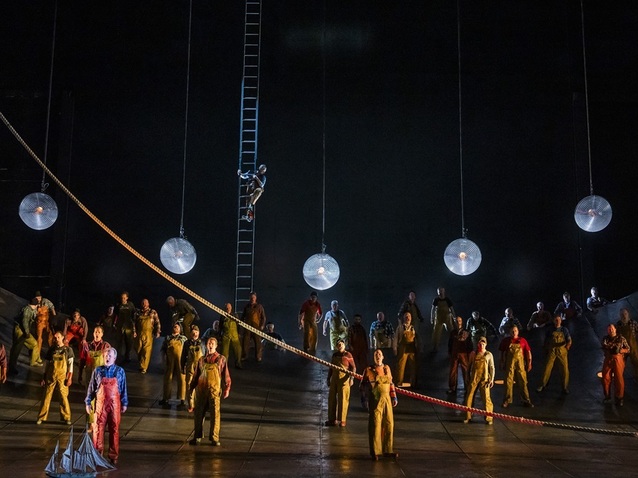

When the curtain rises, we are met with Michael Levine’s bare sloping stage that curves up at the back corners, emulating a ship’s hull or even a sail while also providing a suitable basis for the land scenes. Ladders and ropes cross the stage creating eye-catching diagonals, and the fact that the Dutchman and Daland’s crew put the two main ropes in place reveals how the lives of those aboard both ships suddenly become intertwined.

On land, the stage is filled with rows of sewing machines and a gangway, and David Finn’s lighting is generally kept low throughout. This hints at the ghostly mystique of the scenario, but also serves more specific purposes. The stage is so vast that even performers of the calibre to be found in this revival would struggle to fill the area on their own. By dimming the lights, so that during ‘Die Frist ist um’ the Dutchman acts as a sole beacon of light in a dark void, all problems are overcome. Similarly, in the Dutchman’s main encounter with Senta, a single hanging lamp seemingly provides the main source of illumination. This prop makes the meeting feel akin to an interrogation, albeit a very mild one, which is entirely fitting since the Dutchman is ultimately ascertaining whether Senta will be true forever.

Elisabet Strid (Senta), Toby Spence (Erik), The Flying Dutchman © ROH 2024. Photo by Tristram Kenton

Sir Bryn Terfel played the Dutchman in the original 2009 production, and has appeared in every revival apart from one since. He is strong from the outset as his first appearance sees him obey Wagner’s instruction to adopt a gait that is ‘proper to sea-folk on first treading dry land after a long voyage’. He utilises his bass-baritone to good effect to portray a figure who has been weighed down for so long by his curse that he possesses an almost otherworldly persona. At the same time, however, he still feels human enough for us to be able to relate to him as a real person. It is consequently possible to believe that redemption is a serious possibility, and that he does stand an outside chance of bringing himself back from the brink.

Elisabet Strid is a highly persuasive Senta as her soprano combines a certain sense of depth with an exquisite purity. Her resulting sound feels entirely befitting of one with an almost spiritual capacity for imagining, and it makes her Act II ballad quite spellbinding. Stephen Milling, with his secure and assertive bass, is a highly accomplished Daland, having also played the part here in 2011. In his portrayal we can clearly see how his eagerness to marry Senta to the Dutchman derives from a basic calculation as to the benefits, but overall this helps us to see him not as a greedy ogre, but simply as hearty and human.

Toby Spence as Erik succeeds in putting an enormous amount of space between himself and the Dutchman in terms of their characters. This helps us to appreciate that Senta’s ‘choice’ (if it is one) between the Dutchman and Erik is not simply between different personalities, but between two philosophies on life. Miles Mykkanen is an effective Steersman, with his ‘Mit Gewitter und Sturm aus fernem Meer’ displaying a pleasing lightness of touch, while Kseniia Nikolaieva reveals immense presence and a sumptuous mezzo-soprano as Senta’s nurse Mary.

Production photo of The Flying Dutchman © ROH 2024. Photo by Tristram Kenton

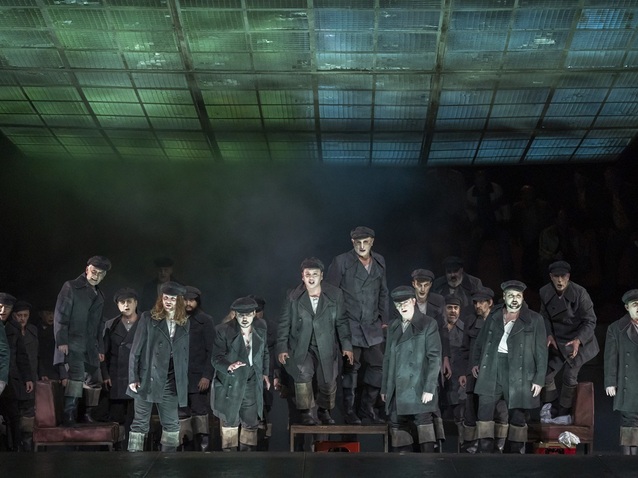

The opera features a second male chorus in the form of a ghosts’ chorus, which, for budgetary reasons, many productions merely represent with offstage voices. Albery actually has them appear in person, which has a shattering effect as there is a big difference between merely hearing the ghosts and having them actually confront us. The fact that we see them interact with Senta, courtesy of movement director Philippe Giraudeau, also has some effect on how the evening plays out. In the scene that immediately follows it is clear that Senta is as committed as ever to going with the Dutchman, but, having caught a chilling glimpse of what life on board will be like, is under no illusion regarding what her obligation entails. She is completely aware that her love for him will not be played out in a comfortable setting, which makes her resolve all the more impressive. All this generates high drama, as does Henrik Nánási’s conducting. There is a considerable amount of weight and depth to the sound that he elicits, but, because everything remains so balanced across the forces as a whole, this ensures that the monumentality with which he imbues the music is never dogged by feelings of turgidness.

By Sam Smith

The Flying Dutchman | 29 February - 16 March 2024 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 02 of March, 2024 | Print

Comments