© Camilla Greenwell

© Camilla Greenwell

Giuseppe Verdi’s Il trovatore of 1853 is based on Antonio García Gutiérrez’s play El trovador. Set in fifteenth century Spain it tells of the noble lady Leonora who is in love with the troubadour Manrico, but is herself loved by the Count di Luna, a nobleman in the service of the Prince of Aragon. The Count’s younger brother Garzia supposedly died in infancy when a gypsy was burnt at the stake for allegedly bewitching him, and the charred body of a baby was then found on her funeral pyre. It transpires, however, that as the gypsy died she ordered her daughter Azucena to avenge her death by killing Garzia, but in her despair and confusion Azucena threw her own baby onto the pyre instead of the noble child. Thus Manrico, who Azucena subsequently brought up as her own, is actually the Count di Luna’s brother, although the Count does not know this.

As the Count and Manrico battle for Leonora it reaches a point where both Azucena and Manrico find themselves imprisoned and facing death. Leonora promises to give herself to the Count if he will release Manrico, and the Count agrees because he does not realise she has taken poison to ensure that she dies before he will ever be able to lay a finger on her. When he discovers her dead, however, he orders Manrico’s death. Azucena is unable to stop the killing, and after it has occurred she declares that Manrico was the Count’s brother, and thus that her mother has been avenged.

Il trovatore (Marina Rebeka, Riccardo Massi, Ludovic Tézier), ROH (c) 2023 Camilla Greenwell

Il trovatore presents a rather far fetched story but, that being the case, it needs to be played straight down the board in order for us to feel its powerful emotions. Applying a silly staging to what could already be deemed a silly plot risks trivialising the entire venture, and unfortunately that is what Adele Thomas’s new production for the Royal Opera, which represents a co-production with Opernhaus Zürich, does. Thomas uses Netherlandish artist Hieronymus Bosch as an inspiration, which on paper sounds a good idea as he was contemporaneous with when the opera’s action is set. However, the obvious aim of such a choice should be to conjure an image of the fifteenth century world that all of the characters inhabit, and the staging fails to do this.

Despite a suitably monstrous face forming the front cloth, as soon as the curtain rises Annemarie Woods’s set merely presents a huge staircase, surrounded by three frames that fall one behind the other. This creates quite a sterile area that, even when brought to life by the activity that fills it, does not really feel as if it is providing a specific context for the action. This leads to clumsy moments such as when Leonora embraces the Count instead of Manrico. With everyone simply appearing on a bare stage, it seems a strange mistake for anyone to make since there is little suggestion of the dark that could have created such confusion. In addition, for us to relate to concepts such as love, jealousy and rivalry, it helps to see these played out in a specific setting, whether that be the original one or another. When they seem to be presented devoid of any real context, the emotions themselves feel more abstract and hence less relatable.

Il trovatore (Ludovic Tézier), ROH (c) 2023 Camilla Greenwell

The main difficulty, however, is that everything is too comical to bring appropriate gravitas to the proceedings. Ludovic Tézier is in tremendous form as the Count di Luna, with his baritone proving to be as rich and secure as it is undoubtedly powerful, but when he sings ‘Il balen del suo sorriso’ the reactions of his retainers take the focus away from him. Their movement is not that great, but as they shuffle forwards and backwards in response to how assertive he is being in the aria, we are being told that this is a man on a stage delivering a big sing, which removes our ability to get inside the mind of one who is revealing the total strength of his feelings for Leonora.

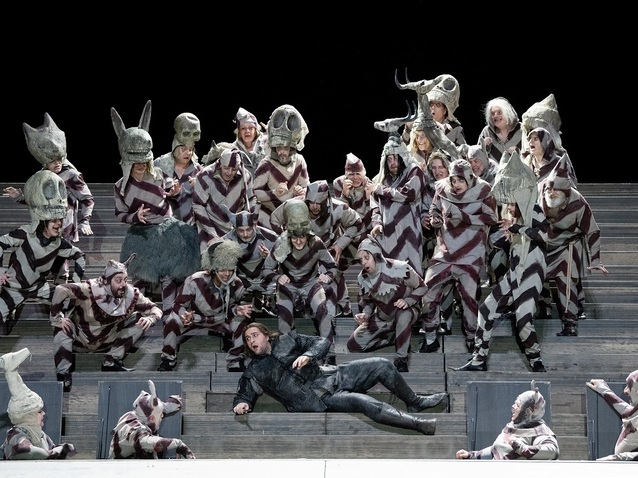

In terms of their actions rather more than their costumes, the male chorus could have come from Spamalot and the female chorus from Sister Act. When Manrico confronts the Count at the end of Act II, half of the latter throw their arms in the air in stereotypical gestures before the scene descends into total farce. This is supposed to illustrate the pandemonium that is unleashed as both sides’ soldiers wish to attack the other, but it does nothing to suggest the seriousness of the struggle between Manrico and the Count for Leonora.

Il trovatore (Marina Rebeka, Gabriele Kupsyte), ROH (c) 2023 Camilla Greenwell

If such an approach is to be taken, it might have been more successful to have gone all out to have produced something that felt totally anarchic. However, the ‘Bacchanalian’ horned dancers that are introduced only elicit small laughs as they linger for a few moments in the course of tripping off the stage at the end of scenes. Similarly, when the actual jokes during ‘Vedi! Le fosche notturne’ do not extend much beyond some chorus members blocking their ears at the sound of the anvils, there is not enough visceral excitement to compensate for the lack of emotion that results from the presentation style.

Even scenes in which there is no mass activity can still have their distractions. When Leonora promises to give herself to the Count the intensity of their interaction is marred by a third character, Luna’s officer Ferrando, considering and weighing up her rosary in the background. All this is a shame because the opera is sung extremely well, but even arias as emotive as those to be found in it feel less so when superfluous action makes it harder for us to focus on, and hence believe in, what is being sung. Where this is the case, however, the fault lies squarely with the direction and not the singers in question. There are indeed some occasions when the soloist is allowed to perform with no ‘accessories’, and when these arise our feelings for what we hear are almost automatically enhanced. Marina Rebeka, with a soprano of sublime beauty and refinement, has the advantage of being able to sing Leonora’s ‘Tacea la notte placida’ totally unimpeded, and it certainly produces dividends.

Il trovatore (Jamie Barton), ROH (c) 2023 Camilla Greenwell

Riccardo Massi is a highly persuasive Manrico, who reveals an expansive tenor that feels warm yet relatively light at the top of the register. There is excellent support from Gabrielė Kupšytė as Leonora’s confidante Ines, and particularly Roberto Tagliavini as Ferrando who asserts a bass of notable security and strength. The real revelation of the evening, however, is Jamie Barton in the role of Azucena. When it is so easy to play the part as a caricature, and in a production that might have appeared to have encouraged such an interpretation, Barton, with her superb mezzo-soprano, succeeds in presenting the gypsy as a very feeling and multifaceted character. In the pit, Sir Antonio Pappano elicits both a smooth and textured sound from the orchestra in a reading that proves to be equally strong on detail and precision. The excellent musical credentials ensure that this Il trovatore ultimately prevails, but it does so very much in spite, rather than because, of the staging.

Rachel Willis-Sørensen sings Leonora and Gregory Kunde plays Manrico for several of the later performances in the run. This production will be broadcast live to selected cinemas around the world on 13 June, with some venues also showing encore screenings on subsequent days.

By Sam Smith

Il trovatore | 2 June - 2 July 2023 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 07 of June, 2023 | Print

Comments