© Richard Hubert Smith

© Richard Hubert Smith

Based on Prosper Mérimée’s eponymous novella, Georges Bizet’s Carmen of 1875 is the story of the ultimate temptress. A gypsy and cigarette factory worker in Seville, Carmen has the power to entice any man she chooses. Once, however, they are besotted with her she quickly moves on, leaving them heart broken and unable to accept what has happened.

In the opera Don José, an army corporal, has almost everything he could ever desire. He has the sweet, loving Micaëla who is more than willing to marry him, the blessing of his mother, a job he is proud of and the opportunity to see his home village. When Carmen decides that she likes him, however, he ends up sacrificing everything he has for her, and cannot accept it when she loses interest in him and turns to the torero, Escamillo.

If Carmen hardly sounds a sympathetic character, she can certainly engage an audience with her allure and steadfast determination to live by her own rules. Freedom is the most important thing to her so that when Don José threatens to kill her unless she says that she loves him, she accepts her fate, preferring death to proclaiming a lie and feeling a sense of imprisonment.

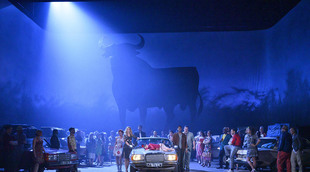

Calixto Bieito’s production for English National Opera first appeared at the London Coliseum in 2012, and now enjoys its third outing there (revived by Jamie Manton). It has always been generally well received although this reviewer, despite believing this to be the best revival of it yet, feels that the more dynamic and raunchy it tries to be the tamer and flatter it becomes. The iconic ‘Les tringles des sistres tintaient’ is a case in point as it sees several people get drunk as they dance on and around a car as if they are throwing an impromptu outdoor party. It hardly generates an outrageous atmosphere, however, and in the process any sense of exoticism, danger or allure associated with the idea of a gypsy dance is entirely lost.

Bieito transports the action to the dying days of Franco’s regime. While this should make the action more relatable by ensuring it remains within some people’s living memory, the production is not always as dynamic as it tries to be. For all ‘La cloche a sonné’ aims to be colourful, the women do little more than sit in a row at the front of the stage as they sing. This contrasts with the men who are far more active behind, and it means that the focus is taken away from the women’s sound. There are a wealth of details that are superfluous to the story, but are designed to aid interest, such as a soldier running around the stage in his underpants during the opening scene. Such additions, however, can prove distracting, and since so many of them take place at the end of scenes they put a severe check on the overall pace when Carmen is an opera where we really need to feel swept along.

The greatest difficulty may be that all of the emotions that the work contains are played out quite directly, when temptation and allure need to bubble beneath the surface in order to make us feel caught up in the intrigue. In this way, Justina Gringyte’s Carmen seems too cheeky, especially when she grins at the thought of having slashed another woman, when we need to feel an ‘ice queen’ who need make no effort for the men to flock to her. Similarly, Ashley Riches’s Escamillo sings ‘Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre’ in a slightly drunken and disheveled state, his shirt hanging out, when there needs to be something more upstanding about the proud torero.

The problems arise from the way in which this production demands the parts to be played, and not from the performances of these individuals. Indeed, both Gringytė’s portrayal of Carmen and her mezzo-soprano feel richer and more developed than they did when she played the same part in the 2015 revival, and she leaves quite an impression. Riches enables his strong and secure baritone to come to fore in the Toreador Song, although possibly the nature of his voice means it feels less powerful at those moments when the direction means he cannot sing completely outwards, while in Act III he reveals just what a smooth sound he can make.

The roles of Micaëla and Don José seem to escape this production placing any detrimental requirements on them, and with her pleasing soprano Nardus Williams captures the sense of a sensitive, loving girl who is strong and courageous in her own way. Sean Panikkar as Don José is the greatest revelation, however, with his extremely expansive sound complementing a performance in which we can really feel his rage boiling over. This is his first appearance at English National Opera, and we can certainly hope there are many more to come. David Butt Philip sings the role for the final two performances.

It is also clear that any difficulties this Carmen faces in terms of pacing are down to the production itself, and not Valentina Peleggi’s conducting, which is highly accomplished as it drives the score while also eliciting a beautifully smooth sound.

By Sam Smith

Carmen | 29 January – 27 February 2020 | London Coliseum

the 02 of February, 2020 | Print

Comments