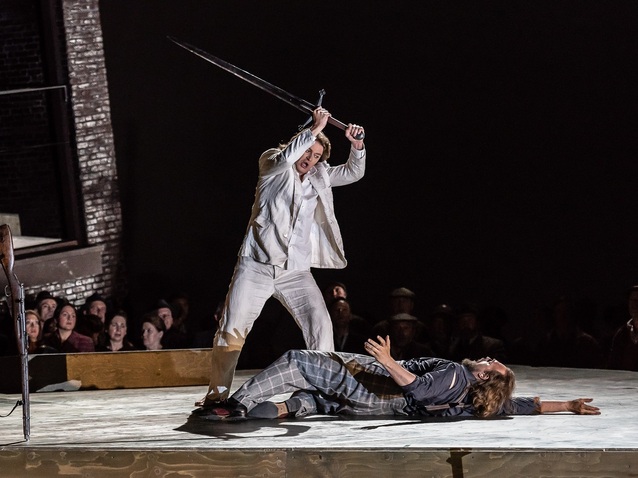

© (C) ROH. Photo by Clive Barda

© (C) ROH. Photo by Clive Barda

Lohengrin of 1850 is the sixth of Richard Wagner’s thirteen operas, and the third he wrote (after Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser) to be regularly performed still. It stands very much at a crossroads in that it harks back to classical opera in some respects, but in others looks forward to the composer’s later music dramas by including leitmotives and being essentially through-composed (although a few distinct arias are to be found within it). It is also the first of his mature operas that he felt no need to revise in the years that followed its creation.

The character of Lohengrin is found in the final chapter of Wolfram von Eschenbach’s epic poem Parzival, written in the first quarter of the thirteenth century, where he is the son of the Grail King. Set in Antwerp on the Scheldt in the tenth century, the opera sees King Heinrich der Vogler arrive in Brabant planning to assemble the German tribes to expel the marauding Hungarians from his dominions. The child-Duke Gottfried of Brabant has gone missing, and his guardian Count Friedrich von Telramund accuses the Duke’s older sister Elsa of murdering him so that she can become Duchess of Brabant. The King is unsure whether to believe the accusation, and decides to test it before God by pitting Telramund against a nominee of Elsa’s in combat, with whoever is victorious proving to be truthful and righteous.

A knight appears on a boat drawn by a swan, agrees to act as Elsa’s champion, and defeats Telramund while sparing his life. The Knight made Elsa promise that she would never ask his name or where he came from, and this holds even when they decide to marry. The King offers to make the Knight Duke of Brabant, in the hopes that he will lead the people to glorious new conquests, but the Knight prefers to be known as ‘Protector of Brabant’. However, the banished Telramund and his wife, the sorceress Ortrud, interrupt the wedding ceremony, accusing the Knight of sorcery and claiming the duel was invalid because he remains anonymous and trial by combat is only open to established citizens. The King dismisses the claims, and the ceremony goes ahead.

However, despite Elsa reconfirming her loyalty, all of this casts doubt in her mind, and on their wedding night she asks the Knight the fatal question. The Knight then kills Telramund when he attacks him, and rushes to the banks of the Scheldt where everyone is assembled for war to tell them that he cannot lead them into battle. He explains that he is Lohengrin, Knight of the Holy Grail and son of King Parsifal, sent to protect an unjustly accused woman. However, the laws of the order require knights to remain anonymous, and if their identity is ever discovered they must return home. As Lohengrin is about to board the swan-boat, Ortrud declares that the swan is Gottfried who she cursed and transformed. The Knight prays, and Gottfried is restored to his human form to become Duke of Brabant. Lohengrin departs for the Castle of the Holy Grail while Elsa, stricken with grief, falls to the ground.

In the first new production of the opera at Covent Garden since 1977, director David Alden sets the drama in a war-torn and politically unstable society. The precise date is deliberately kept vague, but as the location of Brabant falls squarely at the centre of the First World War, that conflict automatically springs to mind. Paul Steinberg’s set presents sloping buildings that could either have been physically damaged by war, or simply describe the way in which the society has been torn to pieces.

The basic concept is sound, but attempts to further it sometimes fall foul of creating visual effects that feel antithetical to the music. For example, Elsa’s beautiful Act I aria ‘Einsam in trüben Tagen’ feels undermined by her being required to struggle and crawl about the stage between verses. Similarly, when the music that heralds Lohengrin’s entrance can feel so enlightening, the act of complementing it with graphics of a flying swan and actions by the chorus makes the entire experience seem too thick.

Nevertheless, certain elements work very well as glances between Ortrud and Elsa in Act II are skilfully managed. These suggest that Ortrud knew the odds were stacked against her and Telramund preventing the marriage, but that their main aim was to cast doubt in Elsa’s mind and reap the rewards later. It is also a nice touch to see Lohengrin and Elsa’s bed chamber bear a painting from August von Heckel’s Lohengrin mural cycle, which can be found in Ludwig II of Bavaria’s Neuschwanstein (literally New Swanstone) Castle.

Alden’s aim is to show how Lohengrin might be the people’s saviour but ‘may also simply be an innocent stranger onto whom the people project their longings, and whom King Heinrich manipulates for his own militaristic purposes’. If this is an idea that might seem impossible to convey in a staging, Alden certainly succeeds in doing so in Act III. The soldiers carry medieval weapons as if to show how Heinrich is harking back to former days of glory, and adopt a new banner that resembles the German black eagle, only a swan now takes the place of that bird. This captures the idea of yearning for the past perfectly because the eagle image appeared on the medieval coat of arms of the Holy Roman Emperors before being reintroduced between 1871 and 1918. As it becomes clear, however, that Lohengrin will not be the one to lead the people these banners come down one by one.

It is still not a vintage staging because, although it is correct to reveal how in this context religion, politics and statecraft are intertwined, like many productions of Tannhäuser, it focuses on the wider political context too much. This is to the detriment of understanding the total piety and religiosity of the culture, which still provides the main explanation for why various people think and behave as they do. Nevertheless, when a thoroughly respectable and frequently interesting staging combines with wonderful musical credentials, the results are very special.

Andris Nelsons’ conducting is outstanding as he captures the glistening and spiritual nature of the music by understanding the interaction, in this context, between precision and fluidity. He also conveys the points behind Ortrud’s darker, more dissonant music with equal skill. Klaus Florian Vogt in the title role reveals a beautifully clean tenor, especially in his Act III monologue ‘In fernem Land’, while Jennifer Davis, replacing a previously advertised Kristine Opolais, is splendid as Elsa, displaying a freshness in her soprano that is lacking in many assumptions of the role. Thomas Johannes Mayer has a strong baritone and suitably malevolent presence as Telramund, Georg Zeppenfeld reveals a magnificent bass as King Heinrich and Kostas Smoriginas a splendid bass-baritone as the Herald. If there is a first among equals, however, it is Christine Goerke whose soprano and portrayal of Ortrud are both simply exhilarating.

By Sam Smith

Lohengrin | 7 June – 1 July 2018 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 14 of June, 2018 | Print

Comments