© Zoe Martin

© Zoe Martin

Written in 1998 to a libretto by Paul Bentley, Poul Ruders’s The Handmaid’s Tale is based on Margaret Atwood’s eponymous novel of 1985. This means that when he wrote it no-one had even heard of Bruce Miller’s television series that aired in 2017. English National Opera first staged the work in 2003, and then introduced a new production by ENO’s Artistic Director Annilese Miskimmon in 2022. This version has now returned, under revival director James Hurley, and, if anything, feels even stronger than before. With six principals reprising their roles from two years ago, and many others being new to them, the cast is superb as they help us to engage with the plight of the clearly oppressed, and with the perspectives of those characters whose actions would, on the surface, make them far from sympathetic.

With some qualifications, the opera follows the same plot as the novel in painting a nightmarish vision of the early twenty-first century, which then still lay in the future. It is a world in which a supposedly stringent, moral orthodoxy has been reasserted, but clearly for self-serving reasons. In this way, the ruling classes, and particularly men, use allegedly Christian messages and biblical passages to uphold an order that serves their own needs. They brainwash those they rule over into accepting and obeying rules that they flout themselves on the grounds that it is safe for them to do what it would be disastrous to allow the masses to pursue. It consequently represents a reversion to the types of order that have existed in many times and places.

The particular focus is a ‘class’ of women known as handmaids. They have committed some form of impropriety, as judged by this society, and been sent on a ‘reform programme’. This sees them enter childless households where they are ritually inseminated once a month by the husband in order to have a baby in place of the wife who is supposedly barren. The handmaids are made to believe, and consequently oft repeat, that there is no such thing as a sterile man, and yet clearly this is not the case. If the wife is unable to have a child, it will often be because the husband is impotent, and yet it is the handmaid who pays the price because if she is also unable to produce offspring she is threatened with expulsion to the ‘colonies’. Again, it is part of a deception that is privately admitted as a doctor offers to ‘help’ a handmaid because he knows the truth, and a wife tries to organise a ‘contingency’ to ensure that ‘her’ handmaid does become pregnant.

Rachel Nicholls, Rhian Lois, ENO Chorus, ENO’s The Handmaid’s Tale 2024 © Zoe Martin

The story focuses on one handmaid who becomes known as Offred (‘Of Fred’ referring to the man of the family to which she is posted). It is told from the perspective of the year 2195 when a symposium looks back on the Republic of Gilead (the name of the ‘theocracy’ that existed in the early twenty-first century) and considers some cassette tapes left behind by Offred. They are the only record of her existence, and provide vital clues as to her life. They do not, however, tell us everything for, while they make it clear she joined an underground resistance movement and attempted to escape over ‘The Wall’ that marked the boundary to the regime, they do not reveal what happened to her.

The novel works well in operatic form since Ruders’ music proves perfect at conveying the sheer sense of emptiness that the handmaids feel on the one hand, and the most climatic moments on the other. In fact, at several shocking points, which include a ritualistic insemination, the score includes a ‘dysfunctional’ version of ‘Amazing Grace’ that heightens both the irony and pathos. There are, however, differences between the opera and novel as Bentley’s libretto tells the story in the third, rather than first, person. Similarly, in the original the reader only learns at the end that the text comes from reconstructing 200-year old cassettes, while here the symposium that frames the drama explains this at the start. This is presumably because it helps if points are made more simply and boldly in opera. The mystery element that works so well in literature could leave audiences engaging less with the characters during the performance if they do not hook in as much to what is actually happening.

Annilese Miskimmon’s staging suits the mood of the piece well with curtains at the back and sides, and generally few props, creating both an enclosed and stark area for the drama. In Annemarie Woods’s set, a further curtain often drops across the stage, which suggests that the handmaids are only being shown what those in power want them to see, and makes us also question what is being hidden. Scenes from Offred’s own past are projected onto this curtain, with her Mother espousing the types of causes that we might typically think of as being fought for in the sixties.

Juliet Stevenson, ENO’s The Handmaid’s Tale 2024 © Zoe Martin

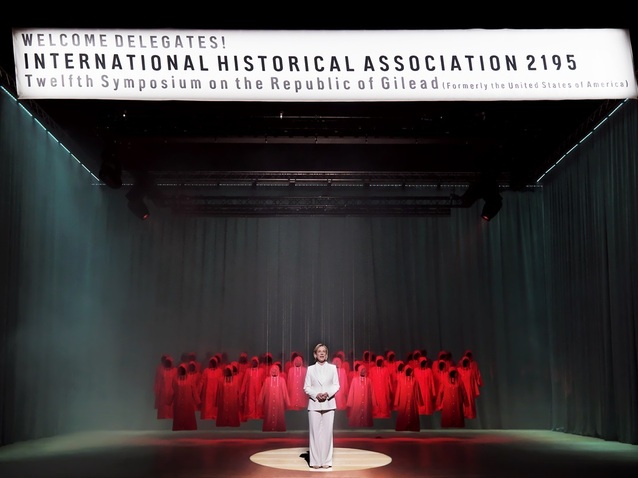

The audience is immersed in the scenario before the opera even begins as announcements are made for them to take their seats not for an opera, but for the symposium that is about to begin. The stage carries a huge banner welcoming delegates to the Twelfth Symposium on the Republic of Gilead, while handmaids’ red hoods hang on the stage, emphasising how in the year 2195 they are, as individuals, unknown, faceless and nameless. Then the speaker Professor Pieixoto, a non-singing role superbly played by Juliet Stevenson, explains what happened in that early part of the twenty-first century and about this one handmaid’s tapes (this is in the original opera), before we are taken back in time to see her for ourselves.

Some scenes are executed especially well so that one sees Offred sing while behind her all of the handmaids queue for their ‘check-up’ with the doctor, each shunting along one chair or standing position as the next goes in to see him. Others are used to show how a pretence is maintained that the child borne by the handmaid really belongs to the wife by putting the latter as centre-stage as is possible during the insemination ritual and birth. The sight of a handmaid vainly reaching for her newborn baby as it is quickly passed to the wife, and she is shunted out of sight, is particularly poignant.

Offred is once again played by Kate Lindsey, whose mezzo-soprano reveals a glistening clarity, even as it is possessed of a wide variety of colours, textures and nuances. She is also highly convincing as someone who has been so exploited that she is used to hiding her own feelings and obeying even the most unsavoury orders without fuss or histrionics. At the same time, she still enables us to see Offred as a real and feeling person, which means that not only do we know that inside she suffers terribly, but that she retains enough spirit to want to work for change.

The strength of the other performances allows us to see many of the characters who it is easy to label simply as ‘evil’ and part of the oppressive system as a little more rounded than that. James Creswell, with his first rate bass, is a relatively sympathetic Commander (the Fred of the family to which Offred has been assigned). While he clearly flouts the rules for his own ends, one senses he is stuck within a system that he detests as much as he exploits. While there is no doubt that when he shows Offred kindness it is predominantly to suit his own needs, the fact he is able to offer it at all suggests he is not entirely without feeling. One is left wondering whether in another time and system, the Commander might well have been a very different person.

Avery Amereau, Kate Lindsey, ENO’s The Handmaid’s Tale 2024 © Zoe Martin

The production also reveals how the insertion of a housemaid into a family affects other relationships within it. This does not mean that the handmaids are to blame, as they are the exploited ones who have been forced into the situation in which they find themselves. Nevertheless, in Avery Amereau’s portrayal of the Commander’s wife, Serena Joy, one can understand how she is left feeling when it seems that her husband is heaping his affections on Offred rather than her. From among the other cast members Rachel Nicholls, with her intriguing soprano, stands out as Aunt Lydia, who runs classes at the Red Centre that ‘trains’ handmaids. While it is hard to believe that she entirely believes the doctrine she forces down others’ throats, in order to do what she does it also seems likely that she has convinced herself to an extent of her own propaganda.

Zwakele Tshabalala is also effective as Nick, the Commander’s chauffeur, and his interaction with Lindsey’s Offred is strong. When they are both in a highly embarrassing situation, her response to a comment he makes succeeds in momentarily breaking the awkwardness in a way that feels extremely natural. There are also excellent performances from Nadine Benjamin, who makes us regret the fact that the part of Moira is not bigger, and Eleanor Dennis as Ofglen. Joana Carneiro’s conducting of Ruders’ enigmatic score is outstanding, while John Findon as Luke, Susan Bickley as Offred’s Mother, Rhian Lois as Janine, Helen Johnson as Moira’s Aunt, Madeleine Shaw as Rita, Annabella-Vesela Ellis as New Ofglen and Alan Oke as the Doctor all play their parts to the full.

By Sam Smith

The Handmaid’s Tale | 1 - 15 February 2024 | London Coliseum

the 05 of February, 2024 | Print

Comments