© Tristram Kenton

© Tristram Kenton

La fille du régiment of 1840 was Gaetano Donizetti’s first opera set to a French language text (by Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Jean-François-Alfred Bayard). Its premiere at the Opéra Comique in Paris has been described as a ‘barely averted disaster’ with the lead tenor apparently being frequently off-pitch, and composer and critic Hector Berlioz slating the piece as he had his own axe to grind with Donizetti. Nevertheless, Berlioz acknowledged that ‘the little waltz that serves as the entr’acte and the trio dialogué... lack neither vivacity nor freshness’, the poet and critic Théophile Gautier suggested that Donizetti ‘is capable of paying with music that is beautiful and worthy for the cordial hospitality which France offers him in all her theatres’, and the opera went on to become hugely popular at the venue. In time it conquered America, Britain and, after a delay of many decades, Italy, and is now very much part of the standard repertoire.

La Fille du régiment ; © ROH 2019. Photo by Tristram Kenton

Set in the Swiss Tyrol during the Napoleonic Wars, it sees a vivandière named Marie serve the Twenty-First Regiment of the French Army. She is loved by the Tyrolean Tonio, who even risks his life by sneaking into the French camp to be with her. The soldiers capture him, and declare he must die, but Marie tells them that he once saved her life when she nearly fell while mountain-climbing, leading them to toast him as he proclaims his allegiance to France. Marie is the daughter of the regiment as its soldiers found her abandoned on the battlefield as an infant, and now every member of it is her father, meaning they all have to give their consent to her marrying anyone. When La Marquise de Berkenfield encounters Sulpice Pingot, a sergeant of the regiment, he recognises that as the name that was on the note found near the abandoned Marie. The Marquise explains that Marie is her niece and takes her away to become a lady, much to the consternation of Tonio who has by now joined the regiment since only a member of it might ever marry its vivandière.

After Marie has lived for several months at the Berkenfield Castle, the Marquise hopes she has made a lady of her, but old habits die hard and when Marie is asked to sing a song by an Italian composer, she is goaded by Sulpice to sing the regimental song instead. In spite of this, she is on the verge of agreeing to marry Duke Scipio of Crakentorp as her aunt wishes when her regiment arrives with Tonio. It transpires that she is not the Marquise’s niece, but rather her illegitimate daughter. This only makes Marie more determined to obey her mother, but at the wedding the regiment storms in at the last minute and reveals that Marie was a vivandière. The guests are offended to hear this, but are then impressed when Marie sings of her debt to the soldiers. The Marquise is deeply moved, admits that she is Marie’s mother, and gives her blessing to Marie and Tonio’s marriage amid general rejoicing.

La Fille du régiment ; © ROH 2019. Photo by Tristram Kenton

Although the piece may represent the epitome of opéra comique, this, in itself, places immense challenges on any director. It would be all too easy to make the staging extremely light, showing no regard for the serious (and classical) dilemmas presented between love and obligation, and wealth versus happiness. At the same time, however, who really wants to witness a production that does not do full justice to the fun that can be gleaned from this most hilarious of creations?

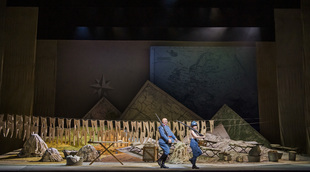

Overall, Laurent Pelly’s 2007 staging for the Royal Opera, now enjoying its fourth revival, achieves a fine balance between bringing out both the piece’s light-hearted and more sober elements. The amusing moments include villagers appearing with saucepans on their heads, soldiers tumbling around while singing of courage and discipline, and guests of the Crakentorps at the signing of the marriage contract looking decidedly doddery. Against this, however, Chantal Thomas’s set has a strong aesthetic quality. It feels slightly frivolous as the rough, mountainous terrain of the Tyrol is created out of large maps that describe the topography, but the predominantly light green colour provides an element of restraint.

Similarly, when Marie is forced to say farewell to her regiment she drags the washing line that bears the soldiers’ garments, thus applying a bitter twist to what was a hitherto comical feature of the set. A sense of perspective is also built into the design so that when Marie in this instance appears towards the back of the stage, she really looks as if she is quite a long way away. The effect is completed by the stage curtain looking like the back of a map that has been unfolded, so that we see one rectangle state that it was created in 1840 (the year that the opera premiered) by a Lieutenant Donizetti!

Sabine Devieilhe as Marie and Pietro Spagnoli as Sulpice Pingot ;

© ROH 2019. Photo by Tristram Kenton

Javier Camarena as Tonio and Sabine Devieilhe as Marie ;

© ROH 2019. Photo by Tristram Kenton

This revival features a strong cast, with the highest accolades going to Sabine Devieilhe as Marie, who combines a tomboyish persona with a certain feistiness. She takes just a little time to warm up, but after this her performance is nigh on perfect as the vivacious exuberance that she frequently conveys in her sound walks hand in hand with the utmost precision in execution. Javier Camarena delivers his high Cs in ‘Ah! Mes amis’ with such aplomb that he repeats them all via an encore of that part of the aria. If, however, his tenor demonstrates the type of robustness that enables him to capture such demanding parts of the role extremely well, it sees others delivered with just a little less sense of polish than would be ideal. Nevertheless, he undoubtedly gives a strong performance, and his rendition of ‘Pour me rapprocher de Marie’ does carry a certain sensitivity. Konu Kim sings the role for the final two performances in the run.

Pietro Spagnoli is an excellent Sulpice Pingot, as his strong baritone combines with a robust presence and jocular persona. Donald Maxwell demonstrates brilliant command of comic gesture and timing as the Major-Domo Hortensius, while Enkelejda Shkoza as the Marquise de Berkenfield gives a priceless performance of ‘Pour une femme de mon nom’, introducing just the right level of histrionics to carry the piece off with aplomb.

The opera also contains a non-singing role of La Duchesse de Crakentorp, mother of the gentleman who the Marquise is hoping Marie will marry, and over the years this production has seen people from a variety of spheres take it on. In 2007 and 2010 the part was given to the comedian Dawn French, while the most recent revival in 2014 saw it performed by Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, who was also given her own aria to sing (‘O fior del giorno’ from Puccini’s Edgar). In 2012 it was executed less successfully by Ann Widdecombe, who has since become a Brexit Party MEP and turned her back on Beethoven as well as opera, but this time the role is taken by the very highly regarded actor Miranda Richardson. Richardson successfully imbues the character with a well-to-do sense of expectancy as she looks bored at the lengthy musical introduction, and demands that no-one scrimps on the booze. She also reveals a great deal of integrity so that while French deliberately went for big expressions and laughs, which was not necessarily a bad thing, she demonstrates more subtlety and thus blends in with everything around her extremely well. To top it off, Evelino Pidò’s conducting is highly persuasive, and the result is a hugely enjoyable evening at the Royal Opera House.

By Sam Smith

La fille du régiment | 8 – 20 July 2019 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 15 of July, 2019 | Print

Comments