© Monika Rittershaus

© Monika Rittershaus

Staatsoper unter den Linden: A Siegfried without passion

Tcherniakov's direction presents a Siegfried without any romanticism or association to the libretto. But the music speaks a completely different language

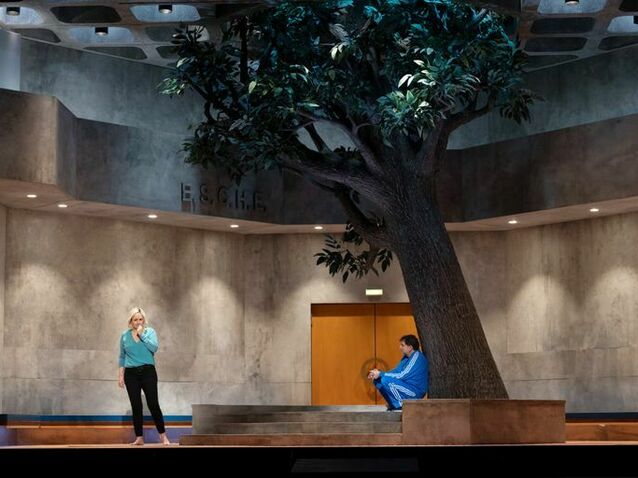

As in Rheingold and Walküre, in the third part of the Ring we still find ourselves in the E.S.C.H.E. Research Centre. That stands for Experimental Scientific Center for Human Evolution, so it has nothing to do with the eponymous ash tree in the opera. And certainly nothing to do with a supposed forest, as envisaged by Richard Wagner. The complex stage set, also by the stage director by Dmitri Tcherniakov, with its movable horizontal and vertical elements, is said to have cost millions. But considering that it is used as a unified stage design for all four operas, perhaps it pays off.

Chronologically, we have arrived roughly in the present. Director Tcherniakov makes Siegfried into a contemporary young man. Costume designer Elena Zaytseva puts him in a blue jogging suit, Mime is in an old cardigan and suspenders, with glasses that are just barely held together with a bandaid, the Wanderer is an old man without an eye patch but with lots of make-up special effects, and costume-wise you could mistake him for a beggar, Alberich is on a walker, Brünnhilde appears in an unspectacular turquoise jumper and black leggings. All very banal, as is the lighting by Gleb Filshtinsky, which can be described as working light.

As in the previous two evenings, the action takes place in the corridors of the research centre. Because these corridors are also supposedly glazed to the audience, the audience is also a voyeur - we all see into these experimental machinations. Even though the glazing is effectively non-existent for acoustic reasons - these frames distance the action and therefore also the emotion. The skeleton structure of Hunding's flat, already familiar from the Walküre, is used here as Siegfried's nursery. Although Lego is not listed as a sponsor in the programme, it could well have been for the fact that the young man is seen here fiddling around with all sorts of large pieces in the unmistakable Lego look. The Lego pieces also have to serve as a forging furnace: Siegfried lights them and - presto - his sword is forged. Not very, no, not at all plausible. Not to mention the fight with the dragon. Instead, texts such as "Phase 2: Immersion and meditation", "Phase 3: Search for the Inner Helper", 'Phase 6: Realisation of an inner wish" are displayed on monitors. By the way, if you open the very elaborate programme book to perhaps get an insight into the director's concept, you look in vain. Instead, you get to see pages and pages of architectural and structural drawings and plans of the E.S.C.H.E. Centre. The viewer feels - rightly - patronised and taken for a fool for not understanding these interpretations. The forest bird is a presumably a young female medical technical assistant who proclaims her message. Brünnhilde wakes up in the sleep laboratory - pushed into the room on a hospital bed by the Wanderer - under a silvery coverlet like those given to athletes to prevent them from freezing to death. In the third act, Siegfried sings Wagner's text, but his body language tells a different story. It is a game for him, a caricature of the feelings he sings about. The great bond with Brünnhilde does not emerge. Both are sitting on the upholstered couch of a waiting room, but they exhibit no emotion toward, not relation with each other, they sing past each other. Only at the very end does Brünnhilde overpower Siegfried in an embrace. We don't find out whether he likes it or not.

Vocally and musically, however, Siegfried is a very satisfying. It may sound old-fashioned, but it is a relief to understand the singers. First and foremost, Andreas Schager as Siegfried, who approaches this role with almost infinite vocal reserves - confident in the high register, radiant and yet with a great deal of intimacy. As Brünnhilde, Anja Kampe is an equal partner to him, quite the youthful, highly dramatic soprano the part prescribes. The Mime by tenor Stephan Rügamer and Alberich by baritone Johannes Martin Kränzle are hard to top in their acting intensity and vocal conviction, although the direction turns them into ridiculous, frail old men. The third old man in the bunch is Michael Volle as the Wanderer with wonderful phrased shading of expression, in stark contrast to his beggarly appearance with worn-out jacket, sandals and walking on a stick. Vocally, Anja Kissjudit fulfils the role of Erda with a warm mezzo timbre, but the stage director puts her in a very passive mould and takes away and indication of a wise, primordial mother. In contrast, the coloratura soprano Victoria Randem as the Waldvogel, is musically quite enchanting and fulfils her role with good diction, happily twittering her rhymes.

In Siegfried, too, Thomas Guggeis in the pit banishes any sluggishness. Instead he tends to stick to brisk tempi, while bringing the listener into a sound world that captivates with its transparency, all wonderfully executed by the Staatskapelle. By the end of the performance, there is again, as with the past two evenings, great rejoicing for the entire vocal and orchestral ensemble.

Zenaida of the Aubris

the 03 of November, 2022 | Print

Comments