© Catherine Ashmore

© Catherine Ashmore

Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades of 1890 is based on Pushkin’s eponymous short story of 1834. Set during the reign of Catherine the Great it sees the officer Gherman initially admire from afar, and then become increasingly obsessed with, the granddaughter of the old Countess, Liza. She, however, is engaged to Prince Yeletsky, and Gherman knows that his lack of wealth means he will never stand a chance of winning her.

He learns, however, that the now elderly Countess carries the nicknames the Muskovite Venus, on account of her former beauty, and the Queen for Spades for a more intriguing reason. Many years ago, she seduced Count St. Germain in Paris into divulging the secret formula that would enable her to win a fortune at cards. She only ever passed it on to two people, and Gherman resolves to become the third in the belief that the wealth he might consequently acquire would enable him to win Liza for himself.

When, however, he confronts the Countess over it, she dies of shock, to the dismay of Liza who believes he was only interested in money rather than her. Then the Countess appears to Gherman as a ghost and tells him the secret and thus the three cards to bet on. Liza and Gherman meet again, but after he starts babbling wildly with obsession and rushes to the gambling table in the belief he cannot lose, Liza, realising that all is lost, commits suicide.

After Gherman correctly names the first two cards, a Three and a Seven, everyone is too frightened to bet against him any more, with the exception of Yeletsky. However, after boldly declaring an Ace, Gherman is shocked to discover that his third card is actually the Queen of Spades, with the Countess having wreaked her revenge from beyond the grave by telling him the wrong card. In despair, Gherman commits suicide asking for Yeletsky and Liza’s forgiveness, while the gathered crowd pray for his tormented soul.

The hook for Stefan Herheim’s new production for the Royal Opera House, a co-production with Dutch National Opera where it appeared in 2016, is the composer himself. At the start captions appear explaining that Tchaikovsky supposedly died of cholera after drinking contaminated water, but that this version of events has been disputed. Instead, it suggests that he may have committed suicide out of despair, having been homosexual and felt forced to marry in order to, in the words of his brother and the opera’s co-librettist Modest, ‘redeem his soul from the moral sufferings that have so plagued him’. In other words, because Tchaikovsky himself was a tortured soul, the opera is autobiographical.

Parallels can certainly be drawn between Tchaikovsky and Gherman, and between the composer and Yeletsky, and between the characters of Yeletsky and Gherman. This production, however, tries to bring all of these out with the result that the thesis being presented feels confused because it bombards us with a complex web of connections rather than a clear set of points with which it is easy to engage.

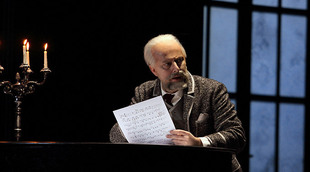

We first see Tchaikovsky before the music even starts, and when the officers start singing he almost jumps out of his skin as he is caught between them. Then Gherman pointedly sings specific lines to him, while the composer scribbles things down as if writing his opera. In this sense, Tchaikovsky could be Gherman, with both being tormented souls and the composer looking back on ‘himself’ in his final days and writing about his life and feelings through his opera. The difficulty here, however, is that it becomes difficult to feel for Gherman, and not only because of the physical distractions provided by the presence and movements of the composer. The very act of seeing Tchaikovsky witnessing Gherman’s actions reminds us that we too are external observers so that we do not feel as intensely as we should for the officer because we are hindered from putting ourselves inside his mind in the moment.

A little way into the evening, however, Tchaikovsky dons a jacket as he steps inside, and sings, the role of Yeletsky, so that the composer is actually the latter. On one level, this makes sense as Yeletsky could be seen as the one who is forced into a marriage that he is not really interested in in order to keep up appearances. However, much as one can grasp the point being made, the act of keeping Tchaikovsky / Yeletsky on stage for the majority of the evening makes us feel viscerally that the story is Yeletsky’s tragedy rather than Gherman’s. As a general thesis there is actually nothing wrong in suggesting that it is. It falls down in the presentation, however, because there are too many moments when Gherman is pouring out his emotions while in the depths of despair, and yet merely feels like a cipher because of all of the other distractions going on around him.

One can appreciate the cleverness in seeing lines that are normally sung to one character being directed towards another, with all of the things this implies. However, because so many additional points are introduced throughout the evening, and because these come from such a wide variety of angles, one is left thinking about everything that is being suggested instead of instinctively feeling anything for any of the characters.

If one can move beyond this, the production looks gorgeous as sumptuous costumes rub shoulders with Philipp Fürhofer’s enticing sets. The latter are constructed so that the room used for the majority of the action comprises several standalone ‘boxes’ that are pushed together to form its walls. These can also be pulled apart, however, to create the more spacious areas, while lights can be switched on inside each to illuminate them and thus create a very different feeling space. The insertion of large mirrors for the ball scene multiplies out the images of the guests to excellent visual effect, while the arrival of Catherine the Great sees the house lights go up as the chorus occupy the stalls and hand out song sheets to the audience so that everyone feels right at the centre of the occasion. There are also a host of excellent symbols such as the large overhead chandelier swinging and billowing smoke as the Countess’s funeral is described, so that it resembles a thurible.

Musically, the evening is strong with Sir Antonio Pappano’s conducting proving extremely astute. It is just a shame that being told that music is tempestuous or dramatic by seeing Tchaikovsky conduct, or sit at the piano playing, it actually makes it feel less so, because it suddenly speaks less naturally to our emotions. Aleksandrs Antonenko and Eva-Maria Westbroek deliver good performances as Gherman and Liza respectively. It may still not quite be Antonenko’s finest hour, but Westbroek’s singing is just one element of her very committed performance. Vladimir Stoyanov, who here plays both Tchaikovsky and Yeletsky, sings the latter’s ‘Ya vas lyublyu’ extremely well, while Dame Felicity Palmer is excellent as the Countess as she simultaneously projects the character as both a weak physical and strong mental presence. John Lundgren as Count Tomsky also delivers some of the best singing of the evening, applying a warmer tone to his sound than he does when playing Wotan in Der Ring des Nibelungen, and thus revealing a great ability to adjust his voice to suit the specific needs of the part. This production will be broadcast live to selected cinemas around the world on 22 January, with some venues also showing encore screenings on subsequent days.

By Sam Smith

The Queen of Spades | 13 January – 1 February 2019 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 16 of January, 2019 | Print

Comments