© Stephen Cummiskey

© Stephen Cummiskey

The story in Claudio Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, performed here in English as The Return of Ulysses, of 1639 is taken from the second half of Homer’s Odyssey. In it Ulysses, King of Ithaca, finally returns to his kingdom following ten years fighting in The Trojan Wars and a further decade lost at sea. His wife Penelope has remained faithful throughout his long absence, in spite of loathsome suitors queuing up to persuade her to forget him and embrace themselves. On returning home, Ulysses defeats all of these rivals in a contest to string his bow, and then proceeds to kill each one. In this way, he is reunited with Penelope, thus ensuring that constancy and virtue triumph over treachery and deception.

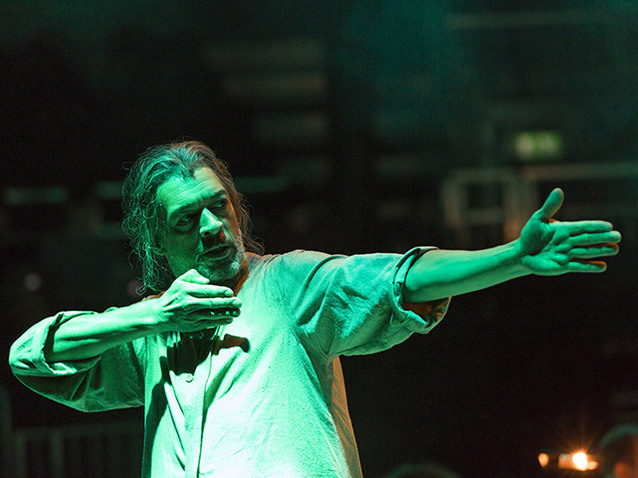

The Royal Opera is performing the work at the Roundhouse, a Grade II listed former railway engine shed, in Camden where it also presented the same composer’s L’Orfeo in 2015. Exploiting the venue’s unique qualities, director John Fulljames ensures that the piece is performed ‘in the round’ in every sense. With the audience sitting in a completely circular formation, the Orchestra of Early Opera Company, conducted by Christian Curnyn, is given the most central point in the resulting arena. This ensures that, both acoustically and metaphorically, everything begins with the music. The ‘pit’ in which the orchestra is situated slowly revolves, and around it is a raised ring that constitutes the performance space. With further rings that feature surtitles and lights hanging above this, the entire stage possesses a vertical momentum that makes the performance area feel like one huge, largely invisible, cylinder.

The monochrome shades that dominate generate a refined aesthetic that appeals to modern tastes. The costumes, on the other hand, come from a variety of eras with ancient armour walking hand in hand with ragged grey clothes and futuristic golden robes. All of this helps to universalise the opera’s themes so that they feel timeless. Given its length, many performances cut scenes and this version has generally chosen to lose those that involve the gods because these characters are not particularly relevant to the plot (with the exception of Minerva who remains), and are less relatable to us today. This proves a wise choice, as it affects the alignment of the production to such an extent that when the characters of Time, Fortune and Love do sing we think of them less as external beings, and instead focus entirely on their essence as entities that affect us all.

There is fun to be had as the shepherd Emaeus’ flock is represented by several strings of white helium balloons, with the bursting of one and an accompanying sound effect signifying a sheep’s slaughter. Similarly, Ulysses’ son Telemachus arrives on the scene riding a tandem with Minerva as smoke rises from the stage. Nevertheless, it is to its credit that the production as a whole does not endeavour to introduce grand effects for their own sake, and remains measured from start to finish. This does not mean it is lacklustre, however, as by the time the performance area is strewn with the bodies of the dead suitors, we feel the sickening sense of destruction that makes us, as modern day observers, wonder if virtue and goodness have really triumphed at all. Indeed, one of the production’s many telling details sees Ulysses and Penelope reunite for a mere moment before he drifts away from her once more on the revolving stage. They may be singing of the reawakening of life and love, but weare left to wonder if they can ever really recapture the past, given all that has happened. The look of sadness on Telemachus’ face would certainly suggest that his thoughts are focused on loss and regret at the perpetuation of violence.

The cast is headed by Roderick Williams who asserts his smooth and sensitive baritone in such a way as to emphasise Ulysses’ psychological depths. Penelope is played by Christine Rice but on opening night, due to vocal indisposition, Caitlin Hulcup sang the role from the orchestra pit and gave an exceptional performance as she asserted her richly hued mezzo-soprano. Rice silently acted the part on stage, and in the process proved just how astutely observed her gestures were.

Catherine Carby is a powerful Minerva, and Susan Bickley a class act as the servant Eurycleia. Samuel Boden asserts his clean tenor as Telemachus, Mark Milhofer is an immensely sensitive Eumaeus and Stuart Jackson reveals both vocal and comic prowess as the parasitic Irus. As the servant lovers Melantho and Eurymachus, Francesca Chiejina and Andrew Tortise work well together as her sweet and striking soprano perfectly complements the sense of ease to be found in his tenor. From among Penelope’s suitors, David Shipley as Antinous stands out for the strength and resonance in his bass.

By Sam Smith

The Return of Ulysses | 10 – 21 January 2018 | Roundhouse, London

Photos credit: Stephen Cummiskey

the 14 of January, 2018 | Print

Comments