© DR

© DR

On 27 February, the Saint Cecilia Academy of Rome will be used as the setting for a concert version of Aida, the Verdi opera, interpreted in particular by Anja Harteros, Jonas Kaufmann and Ludovic Tezier in the principal roles, under the baton of Antonio Pappano directing the Santa Cecilia Orchestra and Chorus. An “ideal cast” for one of the most popular operas, which we often think we are familiar with but which contains deeper subtleties than we sometimes imagine. We shall come back to the mysteries and the scope of this Aida in Verdi's work.

***

It may seem surprising to call Aida an underrated masterpiece. How can this adjective be applied top one of Verdi's most popular works, one of the most frequently staged, especially at the big summer festivals like Verona and Orange? Isn't the title role one of the most sought-after by the great lyric sopranos looking to be remembered by posterity? And yet the public's enthusiasm for Aida is based partly on a misunderstanding that makes it an underrated opera in the real sense. The work immediately suggests an idea of the spectacular and the exotic, with its plot adorned with all the mystery and splendour of Ancient Egypt. The crowd scenes, with theirimpressive choruses and many extras, sometimes accompanied by elephants, strike the imagination in the majestic echo of those famous trumpets whose dazzling notes we've all heard at least once.But reducing Aida to this monumental aesthetic is nonsense. For in fact amidst the recreated pomp of Ancient Egypt a drama unfolds that will end as Verdi wanted it to, on "something gentle and ethereal, a simple goodbye to life."

The Seductiveness of Egypt

It cannot be said that Verdi was very enthusiastic about the new project presented to him by Camille Du Locle in the spring of 1870: the director of the Opéra-Comique came to ask him to compose an opera for the khedive of Egypt. At age 57, a veritable statue of the Commendatore of Italian lyric art, Maestro Verdi had nothing left to prove. He was living most of the time at Busseto, in his villa of Sant-Agata where he continued to oversee the crops and cast only a distracted glance at the proposals for librettos he received constantly. Verdi had already refused to write a hymn for the inauguration of the new Cairo opera house at the time of the festivities for the opening of the Suez Canal on 17 November 1869. But Camille du Locie, who knew the maestro well, having been the co-librettist for his Don Carlos (1867), persisted and insisted.He presented the composer with a brief four-page synopsis set in Ancient Egypt. At the time, French Egyptology was at its peak, because of the work of Mariette, whose importance is recognised worldwide. "Who invented that?", Verdi asked. "It's both theatrical and decorative,, with two or three lovely situations...."The libretto's precise paternity has often been questioned. It appears that Camille du Locie himself based the script on information from Mariette, the French Egyptologist. However that may be, Verdi was ready to set to work, won over by what he considered written by "a very expert hand, that of a man who is very familiar with the theatre."

In order to put the French libretto written in prose by Camille du Locie into Italian verse, Verdi chose Antonio Ghislanzoni (1824-1893), a member of the literary avant-garde movement called "Scapigliatura". The maestro had already worked with him to complete the revision of La Forza del Destino (1862-1869). As was his habit, Verdi was intimately involved in writing the libretto, overseeing Ghislanzoni's work very closely. The musician attached extreme importance to historical accuracy, constantly querying Mariette on the life and morals of Ancient Egypt. He sought out as much information as possible about the period instruments preserved in the museums of Florence and Nimes. All this historical research stimulated Verdi's imagination. His concern for detail went so far as having six valveless "Egyptian" trumpets made, for the famous Triumphal March scene (Act II, scene 2).

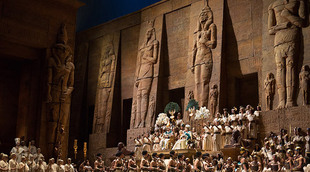

Verdi's opera was to be staged at the new Cairo Opera in January 1871. Mariette was responsible for the sets and costumes, which he had made in Paris based on scale models he created himself. He scrupulously copied Egyptian monuments, such as the interior of the Temple of Isis in Philae, for the third act. For the famous Triumphal March, he took the time to copy the costume designs of soldiers in the tomb of Ramses III.Everything was ready for the opening, but he had not counted on the war between France and Germany, the siege of Paris and the Commune. Verdi composed his Triumphal March just as the Battle of Sedan was taking place in the early days of September 1870. The sets and costumes were stuck in Paris, and it was not until 24 December 1871, when the war ended, that the sets were finally finished and Aida could be staged at the Cairo Opera, with the "most splendid success" according to a telegram sent immediately after the premiere.

Aida was then produced at many other theatres, with the same success. On 8 February 1872, when it was staged at La Scala in Milan, Verdi was called back to the stage thirty-two times! He wrote: "It's probably not the worst thing I ever wrote. The public seems to have loved it. I think it will fill any theatre." In Naples, after the performance, Verdi was carried triumphantly from the San Carlo theatre to his hotel. The procession moved in the light of thousands of torches, and the "magic trumpets" came and repeated the Second Act's Triumphal March right under his windows: it had become an essential "hit"! After this remarkable craze for Aida, it became common practice in Italy to refer to the greatest triumphs as being "Aida-esque".

"Theatrical or Decorative"?

Verdi had immediately referred to the project submitted to him by Camille du Locie using two words that would become unjustly associated with Aida, "theatrical and decorative".

With its grand scenes of spectacular ceremonies enhanced by ballet, Aidais part of the French "grand opéra" tradition, a genre in which Meyerbeer, Halévy and Massenet excelled in the second half of the 19th century. This connection is most evident in the first two acts. In Act 1, the messenger scene is typical of this aesthetic. A long fanfare announces the entrance of the court and the King; a messenger appears and explains what is at stake in the war between the Egyptians and the Ethiopians. War cries ring out to galvanise the assembly, which powerfully asserts Egypt's indestructible might. The overall effect, amplified by the splendour of the score, gives this impressive ensemble enormous theatrical impact.

The famous scene of the Triumphal March in Act 2 is another spectacular illustration of French "grand opéra" and reaches a sort of zenith. This is the most famous tableau in Aïda,, and the work's reputation is often reduced to it alone. The monumental set mirrors the solemnity of the triumphal hymn, "Glory to Egypt", which sounds before the march, played by the famous trumpets designed in Milan by Giuseppe Pelitti according to Verdi's instructions. This is followed by a ballet in Oriental rhythms, expressing the composer's desire to invent an "Egyptian" style of music. Orientalism was then very much in vogue, as witnessed by the success of Bizet's Pêcheurs de perles (1863) or Meyerbeer's L’Africaine (1865).

Within the margins of this impressive set and its exoticism, a drama unfolds that confirms Verdi's predilection for short, passionate stories. Aida indeed appears to be a synthesis between the Italian Romantic tradition and the grandiose aesthetic of French grand opéra. Verdi strove to write intimate scenes and duets carried along by an extremely refined score. The work's monumental aspect and an evident concern for historical accuracy reinforced by the ambient Egyptomania are, paradoxically, counterbalanced by the heartbreak of secret passions.

"Céleste Aida"

The action centres on three characters whose amorous aspirations are thwarted by their respective situations: Aida is a young Ethiopian slave girl serving Amneris, the daughter of Egypt's pharaoh. It will be discovered that the daughter of the King of Ethiopia is hiding beneath the slave's apparent submissiveness. Added to this false situation is a most delicate amorous situation: Aida loves Radames, general of the Egyptian army, who is also loved by Amneris. The mistress and the woman she considers her slave love the same man, but with unequal chances, as the Pharaoh's proud daughter intends to take down her unworthy rival once and for all. When Radames is chosen to lead the Egyptian army against the Ethiopians, Aida is torn between her love and her duty to her homeland, Ethiopia. A terrible dilemma, especially as the one she loves and who loves ger, Radames, soon returns victorious, having taken as prisoner... Aida's own father!

Amneris's implacable jealousy, backed by the intransigence of unyielding priests, will lead to the final scene in which Amneris, prostrate before the tomb in which Aida and Radames have been buried alive, sings a heartwrenching hymn that resonates like the painful acknowledgement of defeat. She failed to win Radames's love, then she failed to save his life after having doomed him out of spite and jealousy to a certain death.

All these passionate yearnings come together and split apart against a background of politics and war. Right from the prelude, Aida's theme, diaphanously sweet and dreamy, is superimposed over that of the Priests, magisterial and disturbing. There is an immediate opposition between the aspiration to love and the implacable power of the Priests that determines the destiny of Egypt. The famous lovesong "Celeste Aïda" sung by Radames comes out of this same opposition: it transforms the glory-hungry warrior into a lover. The languorous dream to which Radames gives himself over replaces his bellicose ardour at the mere mention of Aida's name. The music here takes on the subtlest of nuances.

During the work, all the soloist parts will follow these intimist concerns. Hence, Aida is a complex heroine: by turns emotional young woman, exile overcome by unhappiness, and king's daughter proud of her origins: she defends her love with flamboyant phrasings. This role requires a "lyric" soprano capable of reaching into the sharps and at ease with the belcanto technique, as witnessed by the extreme difficulty of the "Nile aria." The young slave expresses all her nostalgia for her native land in a very elegantly written lovesong that includes a famous "soft" high C.

Amneris, the terrible rivale of "celeste Aida", waivers between the pangs of her unrequited love and the curses inspired in her by her unyielding jealousy. Blinded by her extreme feelings, she does not hesitate to blaspheme against the Priests, whose formidable justice condemns Radames. Amneris is a leading role that has no monologues, which is unusual for a Verdi opera. The character, who performs in ensembles, duets and trios, requires a dramatic mezzo-soprano capable of reaching a soprano's sharps.

Egypt's Pomp in the Solitude of the Tomb

The final scene gives this opera its overwhelming originality. It ends in a murmur, far from the warlike brilliance of the trumpets, a sort of Liebestod worthyof Wagner's Tristan et Isolde (1865). Aida dies of amorous ecstasy, like Isolde. In a sort of luminous serenity, the two loves, walled in alive, die ever so gently with these final words in unison: "Si schiude il ciel" (The sky opens). Left alone, Amneris pleas for peace for the one she sacrificed blindly.

In his The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann evokes this final scene of Aida, underscoring how the power of music transfigures reality: "Two lovers buried alive, their lungs full of contaminated air, were going to perish here, together, or, even worse, one with the other, tormented by hunger, and then decomposition would perform upon their bodies its unnameable work.... Such was the real and objective aspect of things, a side of those things which the heart's idealism does not take into account, which the spirit of beauty and music left triumphantly in the shadows. For operatic hearts like Radames and Aida, the real fate that threatened them did not exist. Joyfully, their voices rose in unison, ensuring that the sky would soon open up before them and, before them, the light o eternity shone."

Catherine Duault

the 22 of February, 2015 | Print

Comments