© DR

© DR

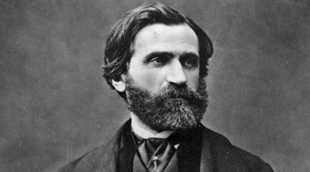

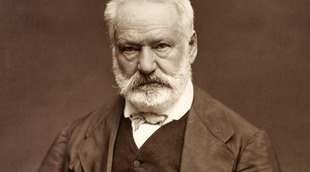

While Victor Hugo’s Le Roi s’amuse experienced only fleeting fame, Rigoletto, its lyric twin, became one of Verdi’s most popular works. Is there anyone not familiar with the Duke of Mantua’s aria “La donna è mobile”? To this essential “hit”, opera lovers will want to add the famous quartet from the final act, “Bella figlia dell’amore”, a brilliant example of polyphony that combines musical and dramatic success. This quartet brought tears to Victor Hugo’s eyes, even though he objected to the idea of seeing “music set underneath his verses”.An opera from the composer’s mature years, Rigoletto marks a turning point in the career of the composer, who went beyond the traditional boundaries of opera to adapt his music writing to the requirements of the drama. At the age of 38, after his famous “years in the galleys”, Verdi was in full possession of his faculties in approaching a subject he had always admired because he found it “great, huge” with its main character, who was “one of the loveliest and proudest creations in world theatre”.

Composing under the Censors

Starting in 1844, when he triumphed with Ernani, Verdi entertained the idea of adapting a new play by Victor Hugo, Le roi s’amuse. In doing so, he was aware that he was taking on a risky enterprise, as Victor Hugo’s play was burdened by a rather demonic reputation. Verdi knew he would have to fight tooth and nail against the censors in order to create the opera for which his inspiration had come in a flash.

The composer had no doubts about the formidable dramatic power presented by what he considered “the greatest story and perhaps the most beautiful drama of modern times”, certain that with “a subject like this, you can’t go wrong”. Verdi was enthusiastic about the dramatic talents of the French author who combined the grotesque and the pathetic, featuring complex, even fascinating characters like this apparently hateful, deformed clown, Triboulet, the hero of Le Roi s’amuse. Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) was the forerunner of this hunchback with a supple spine. His strange ugliness caused disgust and mockery among the courtiers who both feared and despised him. Condemned to solitude and chastity, Triboulet serves as entertainer and go-between for his master, François I, depicted as a carefree and cynical libertine. The jester’s sole comfort is his daughter, lovely as an angel; but in a twist of fate, she was taken from him and turned over for the King’s pleasure. The revenge Triboulet carries out will ultimately turn against him, leading to the death of his daughter, his only reason for living. Debuting on 22 November 1832 on the stage of the Comédie Française, Victor Hugo’s drama was a complete failure. The day after the premier, the coup de grâce came with the prohibition of this work deemed immoral in the France of Louis-Philippe. Verdi would encounter the same disapproval for similar reasons in Venice, even though the censorship was less strict there than in other Italian cities. Fortunately it was a success, and Rigoletto became the first part of what has come to be known as the “popular trilogy” that includes two other works that debuted in 1853: Il Trovatore and La Traviata.

The entire period when he was composing Rigoletto, which began in April 1850, date of the official commission from Venice’s La Fenice, was a struggle, but the composer was justified and rewarded by the triumphant premiere on 11 March 1851. The next day, all of Venice was humming the tenor’s aria, “La donna è mobile”. Convinced that his melody was irresistibly seductive, Verdi had wanted to keep it a secret as long as possible, fearing that someone might hear it before the night of the premiere. The singer did not receive a copy of the score until the last moment.

Having settled with his companion Giuseppina Strepponi in the home he bought in Busseto, Villa Sant’Agata, Verdi worked on his new opera – which he initially thought of calling La Maledizione (The Curse). He entrusted the libretto writing to his faithful librettist, poet Francesco Maria Piave (1810-1876) who, without ever deviating from the original play, worked on tightening up the action to achieve greater dramatic effectiveness. The plot followed the same lines, but the number of acts was reduced from five to three, and the monologues were lightened and the action speeded up. The text chosen was often a literal translation of Victor Hugo’s verses. As was his wont, Verdi closely oversaw this adaptation.

The only significant modifications were the result of the demands of the censors, who started off quite simply by banning the opera, complaining that “the illustrious maestro has chosen to lower his talent to the revolting immorality and obscene triviality flaunted by the subject entitled ‘La Maledizione”! Verdi was furious and threatened to break his contract with La Fenice. The director of public order demanded guarantees, and the composer had to agree to a certain number of changes: a king could not be depicted as depraved and unscrupulous having to deal with a wretched clown”. It was not allowed to evoke a curse that might offend pious souls. It was not allowed to suggest a rape committed by a character exercising absolute power. It was not allowed to have a deformed jester sing: “This will address all the concerns associated with theatrical decency.”. But Verdi exploded: “What am I supposed to write my music to?” After some further new approaches, they reached an agreement: the maestro would have to change time and place and would be allowed to depict an absolute monarch, so long as it was a duke of Mantua. His jester could keep his hump and his pure-hearted daughter on the condition that her kidnapping retained “a character respectful of the considerations owed to the scene”… But he had to give up the title La Maledizione withoutusing Hugo’s title, Le Roi s’amuse, since “it would be derisive of the royal majesty”. Verdi proposed “Triboletto” and then chose Rigoletto, a title borrowed from a French parody of Hugo’s play, Rigoletti or the Last of the Madmen. Perhaps he was also thinking of the French expression often heard in Paris, “rigoler”, which added an aspect of the verb “to laugh” to the jester’s first name. This change in title reflects a change in perspective in relation to the initial piece. The opera would also be more closely centred on the jester’s tragic fate, leaving Victor Hugo’s reflection on the abuse of power aside: “For a king who is amused is a dangerous king”.. Ultimately, Verdi won out, making only minor concessions that in no way altered the profound meaning of his drama.

The Power of the Curse

Verdi constructed his opera around Rigoletto, a doubly cursed figure. The essential spirit of the drama was to be the curse, both the curse of physical deformity and the curse pronounced by Monterone, the offended father, a harbinger of the terrible fate reserved for the jester. In his poignant first-act monologue, Rigoletto is terrorised by the sinister foreboding that haunts him throughout the opera: “That old man cursed me… O men! O nature! What vile blackguard have you made me!...O rage!...To be deformed!...To be a clown… To have nothing, to be able to do nothing but laugh! (…) That old man cursed me!... (…) What misfortune awaits me?” (Act 1, scene 8). Suddenly interrupting a brilliant party, Monterone, whose daughter has been dishonoured by the Duke, comes to demand justice, recalling another frosty apparition, that of the Commendatore in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. The curse uttered by Monterone has the same dramatic reach as the damnation promised to Don Giovanni by the Commendatore.

Associated with the anguish of the curse is an extreme density that punctuates the work like an implacable refrain. This impressively concise theme appears first in the Prelude, orchestrated with brass instruments, widely associated with the affirmation of an ineluctable and menacing power. Listeners should be literally gripped, as they are by the great D minor chord in the overture to Don Giovanni. Built on the repetition of one note, C, this central theme runs obsessively throughout the drama right up to the finale. For Verdi: “The entire subject depends on this curse, which thus becomes the moral”. Achieving perfect unity of construction, the musician brings the opera to an abrupt end with Rigoletto’s cry: “Ah! The curse!” which had already gripped the audience at the end of the first act when Rigoletto realizes that he has unknowingly assisted the kidnapping of his own daughter. From the first note to the last, this movingly stark cry continues like a sinister echo. For Verdi it’s not a question of following up on a set of juxtaposed pieces, making use of one performer or another, or a particular moment. The musical writing is subordinate to an overall vision of the drama: “It is not for me to say whether my music is good or bad, but it is certainly never fortuitous. I try to give it a distinct character that matches the subject”.

Towards a New Musical Dramaturgy

In 1854,in a letter he sent to Francesco Maria Piave, the composer stated that Rigoletto will have a longer life than his first opera adapted from Victor Hugo, Ernani (1844), because it is a work that was “slightly revolutionary, newer in form and style”. He had already stated his preference for Rigoletto a year earlier: “There are some very powerful positions in it, some variety, brio, pathos…”. This search for variety was fundamental for Verdi: he wanted to get beyond the separation of genres that distinguished lyric drama, part of the noble “grand style” of opera buffa, intended to make audiences laugh. The influence of French Romanticism and, uniquely, of Victor Hugo, encouraged the maestro in his desire to broaden the overly narrow field of theatrical representation which, in Hugo’s words, offered only “a mutilated nature “. Verdi aspired to render into music this “vast, real and multifaceted action“ evoked by the French author in the famous preface to Cromwell (18palais 27). Diversifying his musical styles according to the situation was something the composer did constantly in his work. The best example of this face-off of different registers remains the famous quartet from the third act: four characters simultaneously express the most conflicting feelings. Gilda is desperate over the betrayal by her lover, who works on a trivial seduction while Maddalena, sensitive to his advances, is not duped by this licentiousness. At the same time, Rigoletto is choking on wrath and hate.

For the party given at the Duke of Mantua’s palace, Verdi develops themes that combine offhand and disjointed conversations among courtiers. Suddenly Monterone’s magnificent arioso smashes this flirtatious atmosphere. When Rigoletto alone gives himself over to his torment, we hear more of a bravura aria for baritone. A veritable dialogue arises between orchestra and song. The orchestral writing underscores and amplifies, word after word, the jester’s powerful bitterness and rage. A typically Verdian dramatic baritone role, Rigoletto requires a performer capable of adapting his singing to all the changes in the character’s mood. The voice has to follow this great variety of styles.

Gilda’s famous aria, “Caro nome” (act 1, scene 13), deviates from the typical Italian aria, subjugating virtuosity to amorous exaltation and the doubts of an ingenuous girl. Verdi makes the vocal writing conform to the requirements of the plot, no longer worrying about the classic forms of construction. These are no longer “arias” in the traditional sense, but rather theatrical scenes in which the music is shaped solely by expressive force, as in Rigoletto’s great aria “Cortigiani vil razza dannata”, the high point of the work. Rigoletto finds himself in the same position as Monterone. The jester rails against the courtiers, “a vile, accursed race”, then ends up begging them to return his daughter to him, his voice moulding itself to the contradictory emotions that are slowly crushing the character.

Upon its debut, Rigoletto excited audiences but also disconcerted critics who did not know in what genre they should classify a work blending the grotesque and the sublime, light episodes with passionate scenes, and worthy comic characters such as the Duke with tragic heroes like Gilda and Rigoletto. “All the events are born out of a light, dissolute character”, Verdi stressed in 1853, pointing to the Duke of Mantua as the driver behind a terrible story.

Some have noted the implausibility of certain situations, like the moment when the unhappy father discovers his daughter’s body in the sack that was to hide the Duke’s corpse. But the essential aspect of the opera remains the ambivalence of a drama divided between amusement and tragedy. The power and elegance of the musical writing embody the irony and cruelty of fate that plays on human hopes and attachments. This path took the composer all the way to Falstaff (1893). This disturbing melange reflecting life’s contradictions attracted Verdi: “I think it’s wonderful to present this extremely deformed and ridiculous character who is passionate and filled with love inside”.

Catherine Duault

the 09 of April, 2016 | Print

Comments